The making of Attenborough and the Mammoth Graveyard

A MAMMOTH DISCOVERY

Four years ago two amateur palaeontologists discovered a fossilised leg bone in a quarry just outside Swindon. It was a rare and extraordinary find, so when UEA's Prof Ben Garrod heard about it he quickly assembled a multidisciplinary team to see what else they could uncover. The result? An amazingly rich dig, with a mammoth graveyard at its centre.

Now a new Sir David Attenborough documentary on BBC One tells the story of the dig and the many things it uncovered. Prof Garrod explains how it all came together...

The life of any university academic is a mix of many things, and it’s that diversity within the work that I enjoy most about my career. I love teaching my undergraduate students, following wild chimpanzees around African forests, helping conservation charities achieve their goals, and engaging with the public at the fantastic Norwich Science Festival.

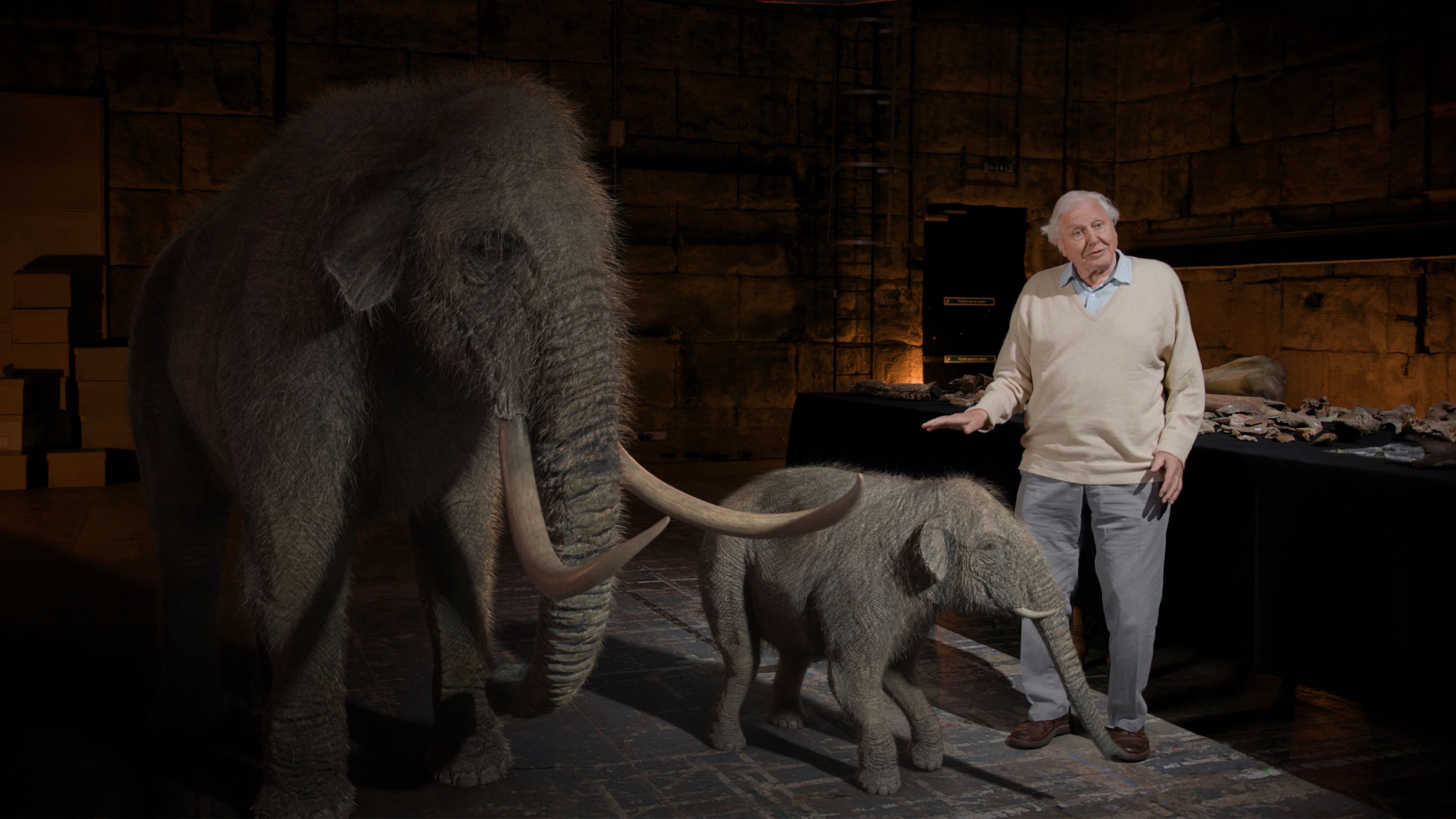

But I must admit that standing in a quarry with Sir David Attenborough - who is a UEA honorary graduate - and a multidisciplinary team of experts as we excavated a whole herd of mammoths was up there with the best moments of my career so far.

Back in 2017 I received a very unusual message. A couple had attended a talk I’d given at a science festival a few weeks before and thought I’d be interested in their discovery. To call husband and wife team Sally and Neville Hollingworth amateur palaeontologists gives little away with regards to just how knowledgeable - and how prolific - this pair are. Like so many people with a passion, they are both enthusiastic and methodical in their approach to finding and preserving fossils.

Did you visit @NorwichSciFest last week? 🦖🌏🦠🧪

— UEA (@uniofeastanglia) November 5, 2021

UEA and @NorwichResearch held over 100 events, talks and activity stands!

Many of the talks are available to watch back ➡️ https://t.co/kz68VnVmHR#ClimateOfChange #NorwichScienceFestival #NSF21 #ProjectChange pic.twitter.com/3MvOyQsHuq

Norwich Science Festival. Prof Ben Garrod pictured right

On this occasion, they were hoping to find a previously unexposed Jurassic bed, left undisturbed for over 100 million years. They’d approached the landowner and set off looking for ammonites, belemnites, urchins, and maybe even the bones from a huge reptilian marine predator or two. What they didn’t expect to find was a much more recent layer above, and for this to be littered with the ice age remains of a number of mammoths.

And where was this new, scientifically important site stuffed full of mammoth remains? Well, think less Siberia and more Swindon. Just outside Swindon, in fact. While it's always great to carry out fieldwork in far flung and remote locations around the planet, it’s worth remembering that there are still incredibly important scientific discoveries to be made, just metres from where you are now, even if those metres happen to be below you.

Prof Ben Garrod, Professor of Evolutionary Biology and Science Engagement in the School of Biological Sciences at UEA

Prof Ben Garrod, Professor of Evolutionary Biology and Science Engagement in the School of Biological Sciences at UEA

"I must admit that standing in a quarry with Sir David Attenborough and a multidisciplinary team of experts as we excavated a whole herd of mammoths was a pretty special moment"

‘Backyard science…’

And so I set about getting a team together, and before grabbing the attention of the nation's favourite naturalist, the man behind Planet Earth, A Life on Our Planet, A Perfect Planet (the list goes on...), I turned to two friends who I knew would be perfect in coordinating the dig.

There is a bit of a niggle within the industry whereby the easiest way to annoy someone who digs up dinosaurs is to call them an archaeologist (they’re not), and the quickest way to antagonise someone excavating an ancient human settlement is to refer to them as being a palaeontologist (they’re also not).

And yet, muddying the water, I decided to approach a team of archaeologists to retrieve the bones of these long dead animals. But there was method to my madness, because alongside some of the large remains lay a beautifully crafted, and sharp, flint hand axe, still capable of separating meat from bone or scraping away fat from a hide.

"And where was this new, scientifically important site stuffed full of mammoth remains? Well, think less Siberia and more Swindon..."

This link to ancient people meant that our team would be led by archaeologists, but would include palaeontologists, and experts in lithics (stone tools), sediments, DNA, lasers and ground-penetrating radar, and a whole host of other areas of expertise.

Lisa Westcott Wilkins and her husband Brendan run DigVentures, a platform pioneering the use of digital technology and crowdsourcing that enable the public to participate in archaeology and heritage projects. It’s citizen science, crowdfunding and collaboration at its best.

We’d met a few years before as I explored the tale of a legendary ‘devil dog’ in East Anglia (a story for another time), and we’d become instant friends. But it wasn’t – just – friendship that brought me back to them, but instead something that would become the hallmark of this unique project – they brought a real interdisciplinary approach to a complex problem, where collaboration was something pivotal to our success, rather than a burden to be tolerated.

Mammoth News!

— DigVentures Archaeology (@TheDigVenturers) November 10, 2021

We're going to be in a brand new BBC documentary with @Ben_garrod and #DAVIDATTENBOROUGH!

Featuring our dig to unearth a mammoth graveyard, some brilliant experts and lots of cool science, the documentary explores life in Ice Age Britain. We can't wait! pic.twitter.com/rgoGIKAlyC

The team has worked on some of the most iconic and most important archaeological sites around, so it made sense for them to head up this new challenge. The deployment of the very rigorous and precise methods and analyses characteristic of modern archaeology would prove invaluable at a site where every minor detail needed to be recorded exactly, especially if we were going to be able to explore any association between the tools and the bones.

Without even stepping foot in the quarry, it was clear that this was an amazing project from the start. It was a multidisciplinary team, with collaborations between numerous companies, organisations, universities, and museums – and an everyday location – emphasising the importance of ‘backyard science’.

The nation’s favourite naturalist

The science is essential, but so too is the inclusion of others from outside the scientific community. If we’ve learned nothing else fighting COVID-19 it’s the importance of empowering the public to engage with the scientific narrative. Sharing science takes many different forms and all work well on some level or another. With science communication and engagement modules run at UEA by Dr Tony Blake, the brilliant work performed by UEA’s Dr Sam Fox with the Youth STEMM Awards, and the constant work from the University's Outreach and Events team at everything from science festivals to Christmas lectures, our own little campus-based microcosm encapsulates just how important, and popular, science engagement is.

So, when I set the wheels in motion to get DigVentures running our newly found secret site, I turned to a mammoth task of my own. I set about getting the discovery made into a BBC One documentary, with the nation’s favourite naturalist – Sir David Attenborough.

It can be an incredibly difficult process to get a film like this made, and time was of the essence. Our biggest hurdle? We didn’t know what was still to be discovered. Sounds obvious, but productions don’t like wild goose chases, and wild megafauna chasers are even more expensive. And so I decided to approach David first, certain that his involvement would help seal the deal. Fortunately we were at a conference together and just before he headed onto the stage, I handed him my phone, open on the photo reel, and let him see the finds from himself. After an excited reaction, he asked me where the site was, and I think it’s fair to say his eyes lit up on discovering it was barely an hour from his home.

That did the trick. It’s harder to turn down a documentary with so many unknowns when the big man himself has already signed up…

And working alongside David is, as I’m sure so many millions of viewers of Planet Earth, A Perfect Planet, et al. can image, an absolute treat. He retains that childlike spark of joy that initially drew so many of us into a career in science. He’d be the first to say he’s just another part of the team and is no more important than anyone else, but it is hard to ignore the moment when you’re crouched down in a muddy trench, alongside other experts and a film crew, uncovering find after find, knowing so many others will get to see this moment – and Sir David Attenborough is right beside you.

Attenborough and the Mammoth Graveyard (C) Windfall Films

Attenborough and the Mammoth Graveyard (C) Windfall Films

Attenborough and the Mammoth Graveyard (C) Windfall Films

Attenborough and the Mammoth Graveyard (C) Windfall Films

"Looking at sediment deposits and the stratigraphy of the site, and examining if marks on the bones could’ve been made by the slicing action from tools, we try to get to the bottom of this prehistoric cold case"

A 200,000 year old cold case

I’ve been very careful to not give too much away so far. You’ll have to watch to find out what happened at this magnificent site just outside of Swindon more than 200,000 years ago.

What I can say is that we found bones from steppe mammoths – and lots of them. We found other species, too, alongside some phenomenally preserved evidence of what the landscape itself would have been like. What’s more, we discovered some breathtakingly beautiful artefacts left by Neanderthal people at a point in our past where the environment was in a very definite state of change due to natural cycles within the climate.

"A BBC documentary is never all slick and problem-free... This is real science on your TV"

We investigate what led to the deaths of these mammoths and look at the possibility of a huge flood event, or whether they were trapped in a viscous muddy bank in this prehistoric tributary of the Thames, or if the Neanderthals themselves were to blame. Looking at sediment deposits and the stratigraphy of the site, and examining if marks on the bones could’ve been made by the slicing action from tools, we try to get to the bottom of this prehistoric cold case.

Related courses at UEA:

A BBC documentary is never all slick and problem-free, and the discussions and ideas are what bring a project like this to life. Fortunately, and quite unusually, we get to show that side of the project too. This is real science on your TV.

This is a project that’s still has so much to reveal. The site itself has many more finds still in the ground and there’s much research and analyses yet to be performed.

While a site like this in the UK reveals so much about what life was like here a quarter of a million years ago, the findings from this discovery may also prove valuable in the development of predictive models that will help us understand – and maybe even offset – the effects of climate change upon our environment in the future.

Prof Ben Garrod is a biologist, conservationist, author, award-winning broadcaster and Professor of Evolutionary Biology and Science Engagement in the School of Biological Sciences at UEA.

Attenborough and the Mammoth Graveyard is on BBC One on 30 December