Fifty years of the Climatic Research Unit at UEA

"THE WORK IS FUNDAMENTAL, FOUNDATIONAL and important"

The Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia has been at the forefront of environmental science since it was founded in 1972. To celebrate its 50th anniversary, hear from students and academics, past and present, about their personal connections to this groundbreaking research institution.

While climate science might appear a relatively young field, we have had at least a basic understanding of the physics of climate change for 150 years. In 1856 the American scientist Eunice Newton Foot discovered that carbon dioxide and water vapour absorbed solar radiation – and suggested that variations in these elements could cause changes in our climate. Three years later, the Irish physicist John Tyndall built on this discovery by identifying the long-wave infrared rays responsible for this heating – and first demonstrated the greenhouse effect.

But it wasn’t until the 1960s, when the first climate models that could demonstrate how the greenhouse effect operated in detail were created, that climatic research began to grow into something like the field we might recognise today. Soon after this, in 1972, Prof Hubert Lamb founded the Climatic Research Unit (CRU) at UEA, with the aim of establishing climate change records “over as much of the world as possible, as far back in time as was feasible.”

Prof Hubert Lamb, the founder of CRU, talks about the impact of climate change in this extract from the 1978 ITV Anglia documentary Changing Climate. Footage sourced from the unique Anglia TV collections held at the East Anglian Film Archive (EAFA) with kind permission of ITV.

Understanding humanity's impact on our climate

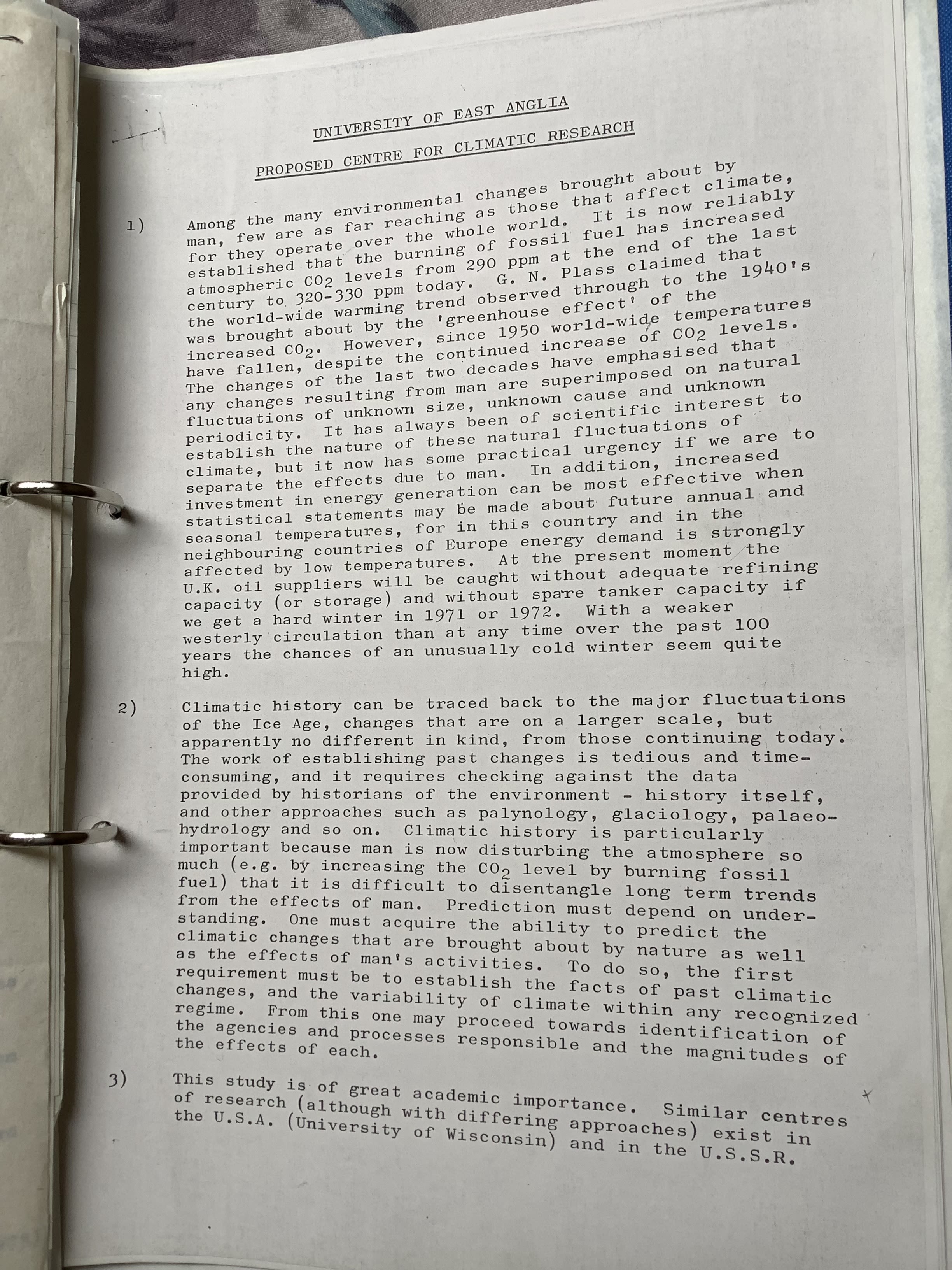

In his proposal to establish CRU, Prof Lamb wrote: "Among the many environmental changes brought about by man, few are as far reaching as those that affect climate. It is now reliably established that the burning of fossil fuel has increased atmospheric CO2 levels… and it has been claimed that the world-wide warming trend observed through to the 1940s was brought about by the ‘greenhouse effect’ of the increased CO2."

And yet, 50 years ago, we did not know how much impact the burning of fossil fuels would have on our planet. We now know that very well, not least through CRU’s research to show how much and how fast the planet has warmed.

When it was founded, the assumption was that CRU might exist for only a decade before the research was wound down or taken up elsewhere. But the realisation – partly due to CRU’s findings at the end of that decade – that human-caused climate change was becoming a global concern led instead to an expansion of the unit. Its scope expanded from establishing historical changes to developing modern datasets that could be used to detect whether human influence could already be seen in the patterns of changing climate

CRU turns 50 this year and its mission is as clear as ever – to improve understanding of how and why our climate changes, using machine learning, statistical and physics-based models to make better predictions of future warming. CRU’s work also helps to make sense of, and reduce, uncertainty in the climate data used to determine worldwide environmental policies.

As well as being a leading institution in climate science, CRU is also a supportive and active community of academics and students. To celebrate its 50th year, staff and students past and present share their experiences of working at the groundbreaking organisation.

Eunice Foote's "On Circumstances Affecting the Sun's Rays" in the American Journal of Science and the Arts, 1856. Eunice Newton Foote, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Eunice Foote's "On Circumstances Affecting the Sun's Rays" in the American Journal of Science and the Arts, 1856. Eunice Newton Foote, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The first page of Prof Hubert Lamb's proposal to establish the Climatic Research Unit at UEA. Image credit: Tim Osborn

The first page of Prof Hubert Lamb's proposal to establish the Climatic Research Unit at UEA. Image credit: Tim Osborn

Looking back at CRU

Jean Palutikof (she/her)

Professor in Climate Change, Griffith University

Prof Jean Palutikof, Griffith University

Prof Jean Palutikof, Griffith University

When did you first become aware of CRU?

Through a job advertisement at the University of East Anglia... I was there for very close to 25 years.

What were you working on while there?

When I first joined it was a project to look at impacts of climate change, to look at various aspects of the British economy. We looked at the impact of climate change on industrial production and tourism, because they were two areas you could really get statistics. It was a statistical analysis of the relationship between the current climate and variations in the index of industrial production and the index of tourist activity. I then gradually moved and worked on, for quite a long time, wind energy and the climatology of wind over the UK.

I also worked with Clare Goodess (Senior Research Fellow, School of Environmental Sciences at UEA) on nuclear waste disposal and long-term variations of groundwater movement as it is what carries radionuclides (unstable chemical elements that emit radiation as they break down) into the soil and environment, how much groundwater is there and how quickly does it move and a lot of that is often down to climate. We looked at very long-term variations and the occurrence of ice-ages because those are timescales that are of interest for the nuclear waste industry and it was absolutely fascinating.

"The work that was done was fundamental, foundational and very important."

The work that was done for the US Department of Energy was fundamental, foundational and very important – there isn’t any doubt about that. It speaks a lot to the way in which the United States funded research, which is something that hasn’t really impacted elsewhere ... if researchers demonstrate value, you will continue to fund the research over the long term ... it did allow them [Tom Wigley, Phil Jones and others] to go on to do something of extraordinary value.

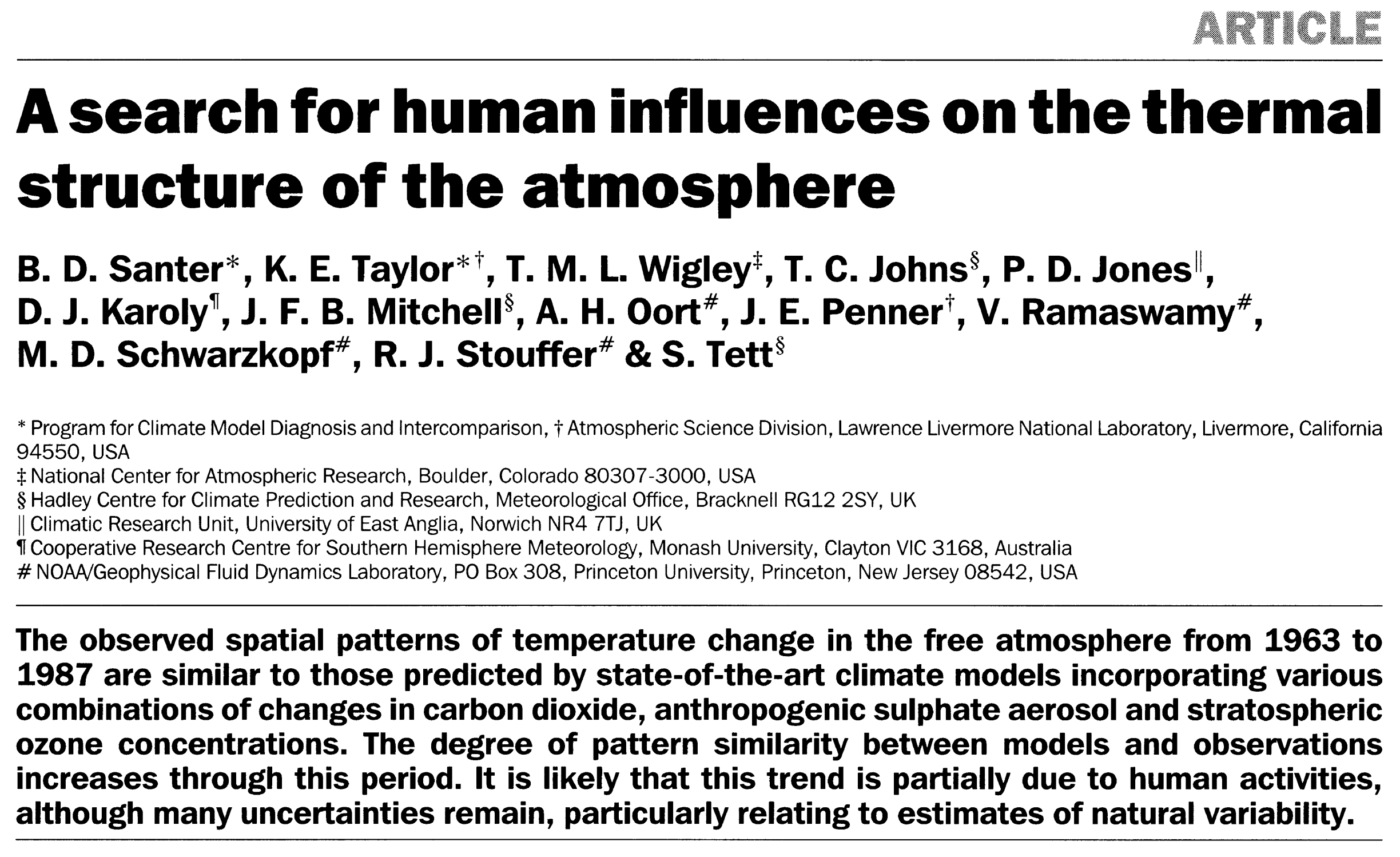

Foundational work: The US Department of Energy provided funding to CRU for over three decades, enabling groundbreaking work such as this 1996 study: "A search for human influences on the thermal structure of the atmosphere”. This research was led by CRU alumnus Ben Santer and involved two CRU directors, Tom Wigley and Prof Phil Jones. It also won the Norbert Gerbier-Mumm Interntional Award Image credit: Nature

Foundational work: The US Department of Energy provided funding to CRU for over three decades, enabling groundbreaking work such as this 1996 study: "A search for human influences on the thermal structure of the atmosphere”. This research was led by CRU alumnus Ben Santer and involved two CRU directors, Tom Wigley and Prof Phil Jones. It also won the Norbert Gerbier-Mumm Interntional Award Image credit: Nature

How collaborative an environment was it?

It was a very collaborative environment... my approach was to create a small group of people I could work with [to stay long term].

How do you think CRU’s work has impacted our understanding of climate change?

CRU has impacted our understanding of climate change, principally, because of the work that’s been done on the instrumental [global temperature] record. There has been other work, like that of Keith Briffa and his associates on tree rings, which was important.

The global temperature record is embedded now – every year the series is updated and every year people sit around and make statements like “this is fourth warmest year on record” ... and so the fact that its become something that’s watched, continually updated and continually reported every year, is really important it just focuses everyone’s mind on what’s happening and doesn’t allow anybody to escape. You can’t forget it.

That global temperature record and all its spin-offs (northern hemisphere, southern hemisphere, land/sea) is a major tool in the toolbox to show people the realities of climate change and that it is human-induced.

Jean Palutikof is a Professor in the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Griffith University, Australia, where she has worked since October 2008. Previously, she managed production of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report for Working Group II (Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability), while based at the UK Met Office.

From 1979 to 2004 she worked at the University of East Anglia, UK, becoming a Professor in the School of Environmental Sciences, and Director of the Climatic Research Unit. Her research interests focus on climate change impacts and adaptation, and communication of knowledge to adaptation decisionmakers.

Prof Peter Thorne (he/him)

Professor of Physical Geography (Climate Science), Maynooth University

Prof Peter Thorne, Maynooth University

Prof Peter Thorne, Maynooth University

When did you first become aware of CRU?

I knew of CRU when I was at high school, with an interest in climate probably before my GCSEs... I knew what I wanted to do. [UEA] was the best place in the country to do BSc Environmental Sciences and then it snowballed from there. I went on to do my PhD [at CRU].

What were you working on while there?

My PhD was on detection and attribution [of climate change] in the free atmosphere, using… state-of-the-art climate models. It involved at the time what felt like very large data sets. How do we know what caused the observed changes that we saw? We took records and tried to compare them to climate models, simulations and disentangle the causes.

What would your career look like without CRU? How might it have differed?

My later jobs were based on what I had been doing at CRU (and the Met Office). My career from PhD onwards has always followed a clear path. I was quite lucky.

How do you think CRU’s work has impacted our understanding of climate change?

CRU was one of the first places that was doing [climate change research] before it became the fashionable, multi-million [pound] enterprise that it is today. When you could count the scientists on your fingers and toes, CRU was very strong in those days... one of the successes of it is that climate science has become more mainstream.

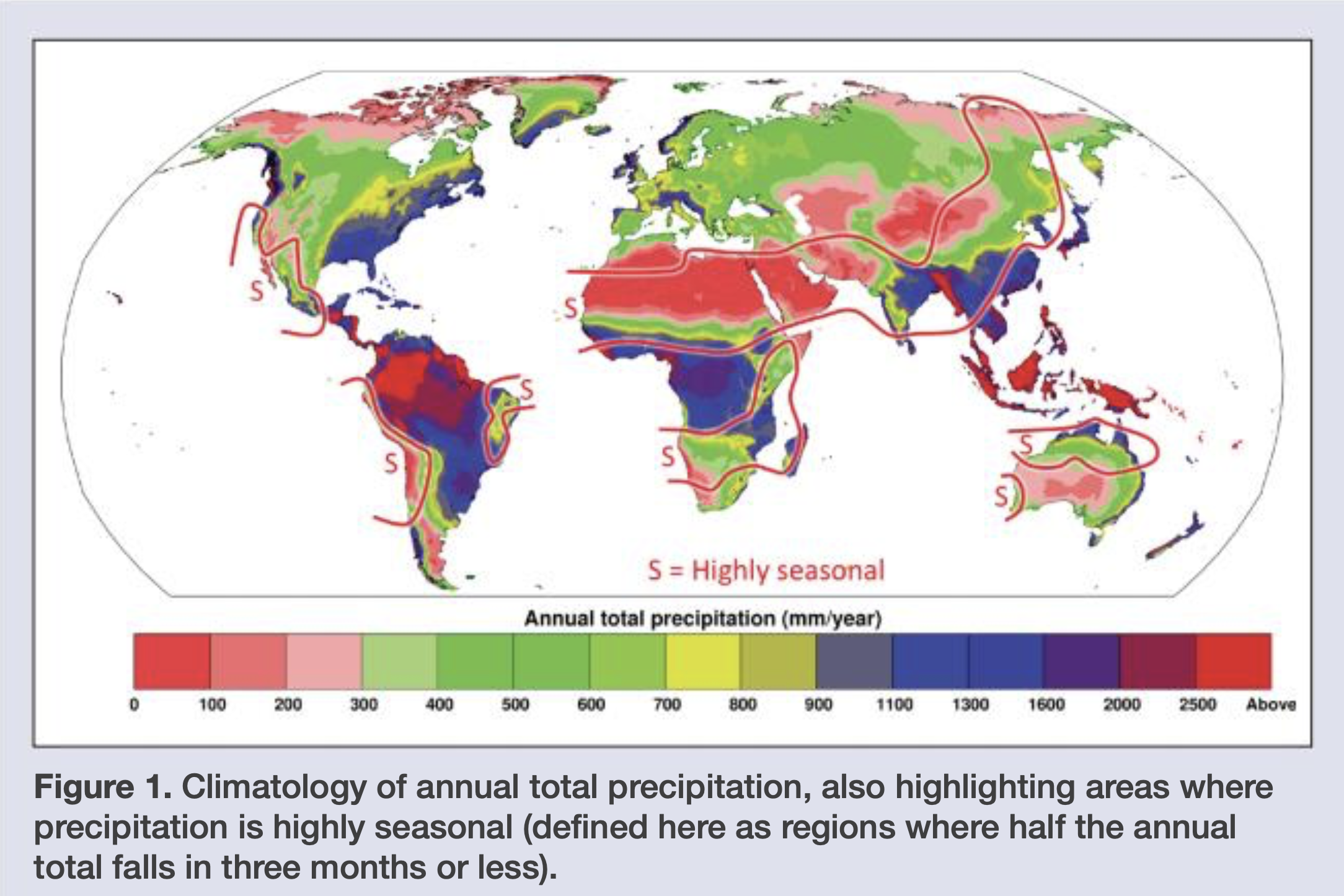

CRU identified early on the need for consistent datasets that covered the whole entire globe. Climate Change is a global phenomenon and these global patterns help us to distinguish between different causes. Image credit: CRU

CRU identified early on the need for consistent datasets that covered the whole entire globe. Climate Change is a global phenomenon and these global patterns help us to distinguish between different causes. Image credit: CRU

“CRU was at the forefront for a very a long time. In terms of understanding of observed climate change in particular, it was leading the way in understanding the regional and national [picture] but also one of the first to really look at the global picture of climate change. You just have to look at the range of things our graduate students have gone on to do.

Prof Thorne studied Environmental Sciences at UEA and went on to a PhD at CRU, which he completed in 2001. He is a Professor in Physical Geography (Climate Change) at Maynooth University in Ireland and Director of the Irish Climate Analysis and Research UnitS group (ICARUS).

Standing strong: The Climatic Research Unit at UEA

Standing strong: The Climatic Research Unit at UEA

CRU in the present day

Sarah Wilson Kemsley (she/her)

PhD researcher at CRU 2018-2022, Now a Senior Research Associate at CRU

Sarah Wilson Kemsley, UEA

Sarah Wilson Kemsley, UEA

When did you first become aware of CRU?

I did physics at university, but my personal interest is in the environment and climate change - and the kind of impact I could have on the world. I thought it made sense to direct my life down that avenue and I started to research the university here and CRU.

What do you work on here?

My PhD research saw the development of a tool that can stochastically generate long time series for a suite of daily weather under a range of climatic scenarios. This allows a user (whether this is in industry or scientific research) to study a range of climate scenarios (including those that have not yet been simulated by climate models) with high computational efficiency and with reduced bias. This may have applications in the study of changes to the occurrence and severity of extreme weather events, as well as producing time series for inputs to hydrological (and alike) impact assessments.

I now work with Peer Nowak, Lecturer in Atmospheric Chemistry and Data Science at UEA, looking at using machine-learning techniques to constrain cloud feedback projections, so again addressing climate uncertainty.”

How collaborative an environment is it?

During the pandemic there were weekly socials on Teams. There is a lot going on now – CRU forums, CRU socials, the CRU garden party, and everyone’s really friendly. It is a social and collaborative environment.

(l-r): Sarah Wilson Kemsley, Andrea Williamson and Tim Osborn enjoy the cakes at the CRU 50th birthday party at the Platation Gardens in Norwich in June 2022. Image Credit: UEA

(l-r): Sarah Wilson Kemsley, Andrea Williamson and Tim Osborn enjoy the cakes at the CRU 50th birthday party at the Platation Gardens in Norwich in June 2022. Image Credit: UEA

How do you think CRU’s work has impacted our understanding of climate change? And what impact do you think it’s had on global efforts to halt it?

Members of staff, both previous and present, have had a lot of impact working with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), as well as producing the global gridded temperature record, the historical record, which is used by scientists all round the world. CRU has had a clear impact on the wider scientific community.

"From aged 21 I’ve been involved with life here. CRU’s really shaped who I am as a researcher, as well as a person."

What would your career look like without CRU? How might it have differed?

I feel like I owe a lot to CRU and especially Tim [Osborn, Director of CRU] for taking someone from a different background who hadn’t proven themselves with a Masters. I do feel really grateful for that. From aged 21 I’ve been involved with life here. CRU’s really shaped who I am as a researcher, as well as a person.

Manoj Joshi (he/him)

Professor of Climate Dynamics, UEA

Prof Manoj Joshi, UEA

Prof Manoj Joshi, UEA

When did you first become aware of CRU?

My first engagement with CRU was whilst I was working at the University of Reading 20 years ago. I got in touch to get data on the global temperature record.

What do you work on here?

I work on climate dynamics and climate modelling: how we understand the physical climate and how it may change in the future. If we want to understand what's happening in the future, then we have to combine observations, theories and model projections and that's what CRU works on: building up a more complete picture of the climate, what it did in the past and then what it's going do in the future.

But you have to turn that into information people find useful and CRU has also done that e.g. sea level rise around Norfolk for example, or how many days above a certain rainfall threshold are we going to get?”

How collaborative an environment is it?

CRU, the School of Environmental Sciences, and the Centre for Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences are pretty collaborative. I think in an area like ours you have to collaborate with other people; the people who do the modelling have to collaborate with the people doing the observations and vice versa because that's how you build up your best understanding.

It's also about the atmospheric scientists collaborating with the oceanographers, collaborating with hydrologists etc. It's across disciplines and that's one area where CRU being part of Environmental Sciences is great because it houses a very wide range of people and encourages that interaction.

"The interdisciplinary environment here has helped… the campus is lovely, Norwich is nice, and CRU is a supportive environment."

How do you think CRU’s work has impacted our understanding of climate change?

The global temperature record helps to put 21st century climate change into the context of the past, and that’s very important because that tells you how impactful climate change will be. CRU has also worked on climate services and impacts.”

What would your career look like without CRU? How might it have differed?

If I had not come to CRU, I would still be at the University of Reading most likely. So, coming here has meant that I've become an academic, so I was able to work on a whole number of basic science questions. The interdisciplinary environment here has helped with that … the campus is lovely, Norwich is nice, and CRU is a supportive environment to work in.