Norwich Works:

The Industrial Photography of Walter and Rita Nurnberg

'Norwich Works', an exhibition at Norwich Museum and Art Gallery, showcased the stunning photographs of Walter and Rita Nurnberg. The collection, focusing on industry in post-war Norwich, applied glamour and drama to an era of steel and practicality.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Steel stockyard. Steel, Boulton & Paul, Riverside Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1947-8 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Between 1948 and 1961, husband and wife Walter and Rita Nurnberg photographed the factories of Norwich and their workers. These images, which owe as much to Rita’s skilful processing as they do to Walter’s original compositions, go beyond the documenting of industry. Meticulously choreographed photographs of the factories are infused with the high modernism of the Bauhaus, whilst striking portraits of workers lean into the glamour and beauty of cinema’s golden age. From the time-worn faces of the master artisan to the teenage apprentices shining with enthusiasm, the Nurnbergs’ photographs are both local history and enduring works of art.

The ‘Norwich Works’ exhibition at Norwich Museum and Art Gallery. ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service.

The images were on display from October 2023 to April 2024 in the 'Norwich Works' exhibition, curated by Dr Nick Warr, UEA, and Dr Simon Dell, at Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, for the first time since the Nurnbergs' pioneering 'Camera in Industry' display which took place at the Castle 70 years ago. The exhibition highlighted the Nurnbergs’ distinctive and influential photographic practice, focusing on the extraordinary visual record they created of Norwich striving to rebuild itself economically after the Second World War. It included over 130 original photographic prints representing three key Norwich industries: shoemaking at Edwards and Holmes’ Esdelle Works; steel construction, woodworking, and wire netting at Boulton & Paul’s Riverside Works; and sweet-making at Mackintosh-Caley’s Chapelfield Works.

The ‘Norwich Works’ exhibition at Norwich Museum and Art Gallery. ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Steel stockyard. Steel, Boulton & Paul, Riverside Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1947-8 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Steel stockyard. Steel, Boulton & Paul, Riverside Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1947-8 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Steel stockyard. Steel, Boulton & Paul, Riverside Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1947-8 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Steel stockyard. Steel, Boulton & Paul, Riverside Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1947-8 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

The ‘Norwich Works’ exhibition at Norwich Museum and Art Gallery. ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service.

The ‘Norwich Works’ exhibition at Norwich Museum and Art Gallery. ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service.

The ‘Norwich Works’ exhibition at Norwich Museum and Art Gallery. ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service.

The ‘Norwich Works’ exhibition at Norwich Museum and Art Gallery. ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service.

From Berlin to London

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Check weighing and closing cartons. Mackintosh Caley, Chapelfield Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1958 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Walter Nurnberg was born in Berlin in 1907. He grew up wanting to be a musician, but upon leaving school he followed his father into banking. In 1931, he was working with a consultant who was the finance director of the Reimann-Schule, a private school of art and design. Nurnberg visited the classrooms and the experience was decisive; he was of independent means and abandoned his first career to enrol on the school’s newly founded photography course. Established by Albert Reimann in 1902, the Reimann-Schule was a pioneer in offering courses that combined studio instruction with practical workshop experience and a commitment to training ‘in the service of trade and industry’.

"Their distinctive style of black and white images transformed the image of post-war British industry."

Nurnberg took these practices with him when he made the decision to move to London in 1934. He lodged in Finchley with Johannes and Kathe Kern, and became closely acquainted with their daughter Ilsa Rita, who was born in Fulham in 1914 and was training as a photographer and graphic designer at the commercial studio Gee & Watson. She and Walter married in 1941 and, after the Second World War, the Nurnbergs concentrated their collective skills in documenting and celebrating the workers of Britain. Over the subsequent decade, the Nurnbergs made photographs for many of the nation’s most significant companies and their distinctive style of black and white images transformed the image of post-war British industry.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Check weighing and closing cartons. Mackintosh Caley, Chapelfield Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1958 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Check weighing and closing cartons. Mackintosh Caley, Chapelfield Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1958 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Reinventing Industry

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Power riveting. Steel, Boulton & Paul, Riverside Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1947-8 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

The British industries which Nurnberg was to photograph in the late 1940s and early 1950s were all affected by the outbreak of war. They had to adapt to attempt post-war recovery in tandem with the project of social renewal – the creation of a welfare state. Walter and Rita introduced a number of innovations into the field known in the interwar period as ‘technical photography’. Earlier photographers of industry were content to show factories, and where workers were included in images their role was normally reduced to demonstrating an operation or showing the scale of a machine. The Nurnbergs repurposed the skills they had developed in advertising to create more dramatic images to present workers as well as machines and products. Their earliest commissions for this new type of imagery were from the brewing, textile and steel industries.

"These exhibitions were motivated by a distinctive combination of pedagogical conviction, civic responsibility and astute business acumen."

Between 1947 and 1954, Walter and Rita programmed, curated and installed touring exhibitions in over 25 venues across the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. These exhibitions were motivated by a distinctive combination of pedagogical conviction, civic responsibility and astute business acumen. Instead of directly approaching firms, the Nurnbergs devised a traveling exhibition, consisting of the latest examples of industrial photography. These exhibitions were then offered to the public libraries, museums and art galleries of industrial towns for free.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Power riveting. Steel, Boulton & Paul, Riverside Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1947-8 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Power riveting. Steel, Boulton & Paul, Riverside Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1947-8 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Norwich Works

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Stitching shoe linings. Edwards & Holmes Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

Between July 1940 and November 1943, the Luftwaffe inflicted catastrophic damage on the city of Norwich. The air raids resulted in the death of 340 people, with 1,092 injured, and over 2,000 houses destroyed. The bombing also devastated the city’s commercial and industrial infrastructure, with 130 factories, shops and warehouses either obliterated or damaged beyond repair. During the Baedeker Raids of April 1942, which were a response to the Royal Air Force’s strategic targeting of German factory workers, 225 lives were lost in a concentrated attack. Not only did these raids take a considerable toll on Norwich’s historic buildings, but they also inflicted considerable damage on industrial sites that had established themselves in and around the city’s medieval walls.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Hand-dipping marzipan fourrées. Mackintosh Caley, Chapelfield Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1958 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

The Nurnbergs first visited Boulton & Paul’s Riverside Works, the second largest engineering firm in Norwich, and one that was heavily damaged by German bombs, in late 1947. Evidence from the numbered negative books in the Nurnberg Archive, housed at the National Science and Media Museum, reveal that the Nurnbergs’ next commission in the city involved the photography of the newly reconstructed premises of Edwards & Holmes, a shoe manufacturer situated on Drayton Road. This factory, known as Esdelle Works, had suffered complete destruction from incendiary bombs in 1942. In 1950, they visited the Mackintosh-Caley Chapelfield Works, sweet makers who had just commenced ‘off ration’ production.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Stitching shoe linings. Edwards & Holmes Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Stitching shoe linings. Edwards & Holmes Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Hand-dipping marzipan fourrées. Mackintosh Caley, Chapelfield Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1958 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Hand-dipping marzipan fourrées. Mackintosh Caley, Chapelfield Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1958 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Objects

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Shoe lasts. Edwards & Holmes Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

“If one were to walk into a factory in full production, have a look around and then proceed to talk about Art, one would be confronted by an amused but marked scepticism. If, however, one were to go further and extol the inherent beauty of industrial processes, the excitement of moving machinery and the allure of forms and textures, this scepticism would turn into the firm belief that such appreciation of ordinary things can only be the hall-mark of eccentricity.

Yet in our private lives, most of us have very personal attachments to the things around us, and we surround ourselves with objects, not only because of their usefulness but because they satisfy our sense of beauty. Why then does this particular relationship between man and matter become suspended during working hours; why does it seem so difficult to see beauty in the detailed facets of industry?”

Walter Nurnberg, The Allure of Things (1962).

"The life they wish to bestow upon these things is a strange one."

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Setting saw teeth. Wood-working, Boulton & Paul, Riverside Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1947-8 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

The Nurnbergs’ relationship with the commonplace objects that surround us possesses an alchemical quality, as they seek to employ the chemistry of photography to bring life to this inert matter. However, the life they wish to bestow upon these things is a strange one. While the camera’s split-second exposure permanently freezes the mechanical motion of the objects, each image exudes a distinct sense of animation. This aspect is not exclusive to the Nurnbergs’ photography, but Walter Nurnberg’s approach to achieving it is rather unconventional. Instead of relying on traditional techniques like motion blur to convey dynamism, the objects he captures on film exhibit a profound stillness akin to a disturbed animal anxiously anticipating its opportunity to escape. The fastidiously realised surface texture of the objects also accentuates this idea of them belonging to a peculiar creaturely realm.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Shoe lasts. Edwards & Holmes Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Shoe lasts. Edwards & Holmes Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Setting saw teeth. Wood-working, Boulton & Paul, Riverside Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1947-8 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Setting saw teeth. Wood-working, Boulton & Paul, Riverside Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1947-8 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Hands

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Tying off Wire netting. Boulton & Paul, Riverside Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1947-8 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

“We all know that hands have always challenged the imagination, not only because they divulge character and human nature undisguised, but they have, throughout the ages, held a special symbolic significance. But above all, hands bring the human touch into an often arid world of science and technology. They will remind us all that even in a world of automation and mechanical handling, the hand of man is still operative, and remains not just a symbol but a living expression of human genius and adaptability.”

Walter Nurnberg, The Human Touch (1962) .

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Card patterns. Edwards & Holmes, Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

The hand-studies that feature prominently in the Nurnbergs’ practice serve as a reminder, especially in the age of digital photography, that for Walter and Rita, photography was a craft created with their hands. Each aspect of the photographic process, the delicate manipulation of the camera mechanism, the mixing and application of the processing chemicals, requires a high level of manual skill. While Nurnberg’s guidebooks may explicate the technical aspects of photography, the artisanal dexterity which transforms photography into an art form finds its expression in his industrial hand portraits. In addition to playing an illustrative or symbolic role in the images, Walter Nurnberg’s emphasis on the fingers and palms of the factory workers reveals the tactile essence of the tasks being portrayed.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Tying off Wire netting. Boulton & Paul, Riverside Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1947-8 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Tying off Wire netting. Boulton & Paul, Riverside Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1947-8 ⓒ Norfolk Record Office.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Card patterns. Edwards & Holmes, Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Card patterns. Edwards & Holmes, Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

Portraits

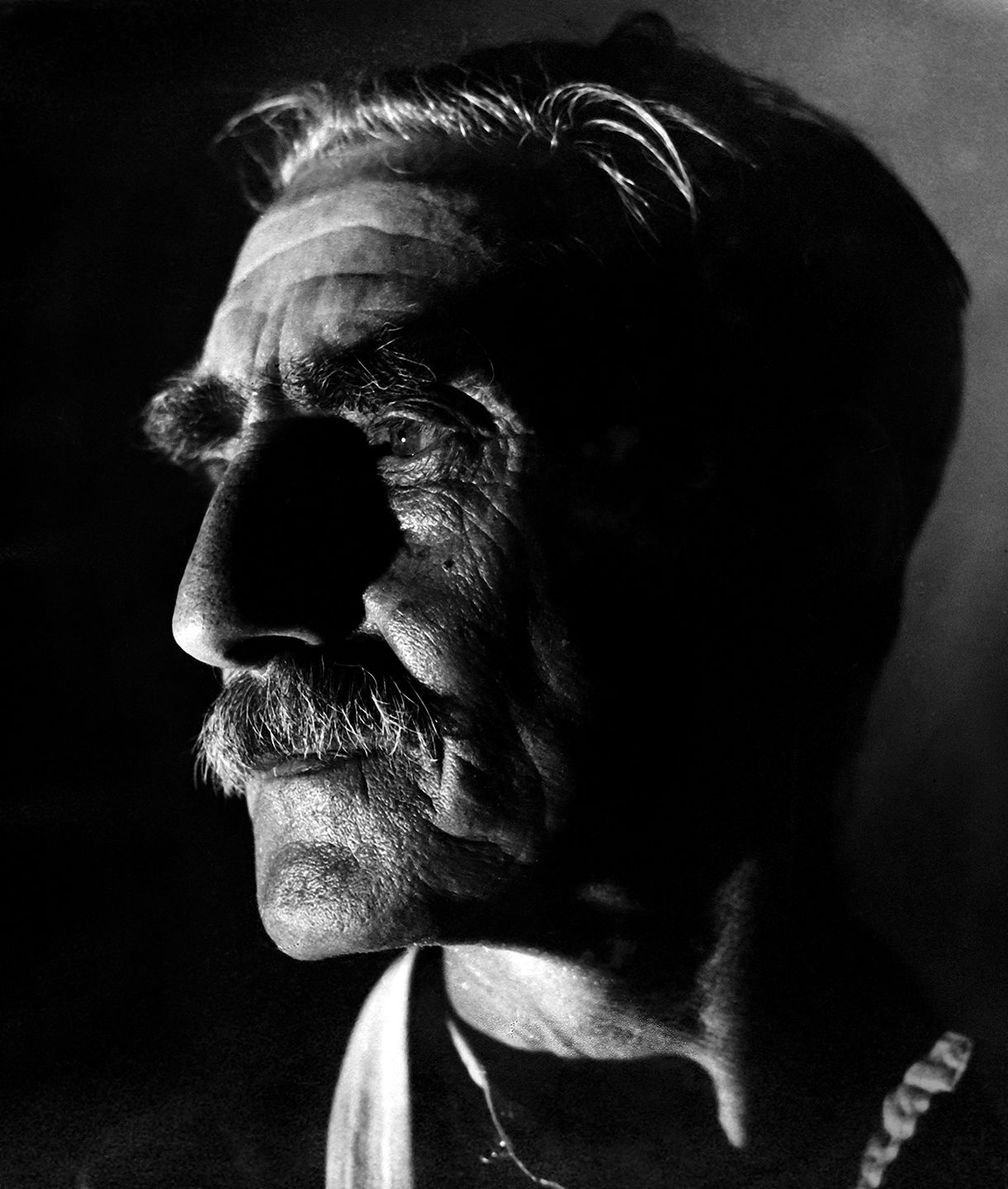

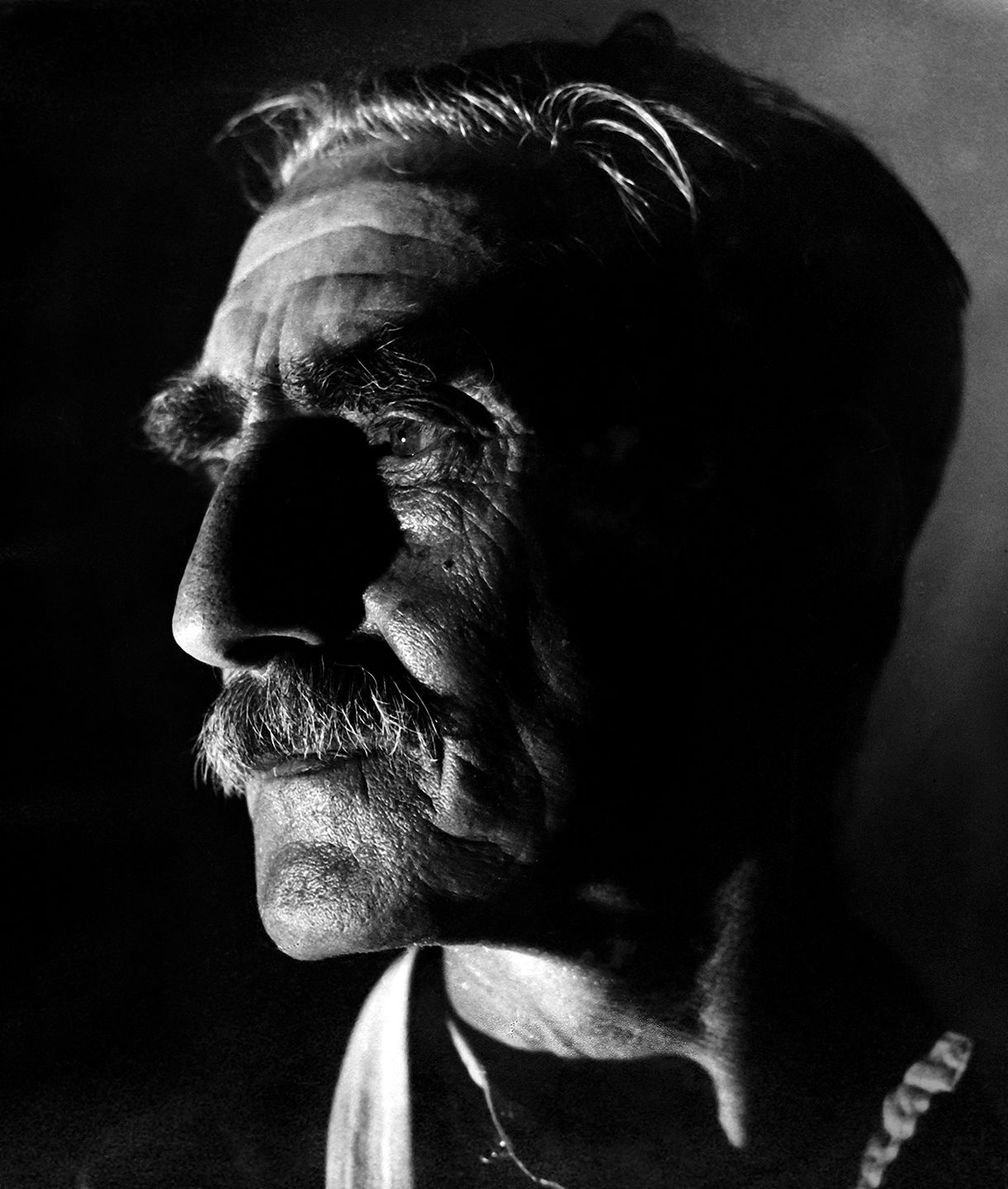

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Portrait of worker. Edwards & Holmes, Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

“We do not perceive the human face as a static form of features and contours, but as something dynamic – a conglomeration of multiple fractions of expression. Consequently, a literal reproduction of facial contours will never satisfy our sense of appreciation and we have to aim at presenting a sensorial likeness which grants insight into the character and emotional qualities of a person.”

Walter Nurnberg, On Portraiture (1941).

"These photographs are not intended to illustrate specific sociological or political ideas but rather serve as expressions of human individuality"

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Portrait of worker. Edwards & Holmes, Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

The Nurnbergs’ portraits of factory workers are remarkable for various reasons. First, their keen focus on surface details such as skin, hair, and clothing sets the work apart from the flattering glamour of commercial studio photographers. Second, the faces of the British working class are captured in a way that deviates from conventional social reportage; these photographs are not intended to illustrate specific sociological or political ideas but rather serve as expressions of human individuality, both in front of and behind the camera. Yet what is not immediately evident is the technical distinctiveness of the portrait photography within the Nurnbergs’ body of work.

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Portrait of worker. Edwards & Holmes, Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Portrait of worker. Edwards & Holmes, Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Portrait of worker. Edwards & Holmes, Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

Walter & Rita Nurnberg. Portrait of worker. Edwards & Holmes, Esdelle Works, Norwich. Gelatin silver print, 1948 ⓒ Norfolk Museums Service (Museum of Norwich).

Adapted from the Norwich Works catalogue, edited by Nick Warr with contributions by Simon Dell and Elizabeth Elmore.

The 'Norwich Works' exhibition was a partnership between Norfolk Museums Service, University of East Anglia, Norfolk Record Office and The East Anglian Film Archive. It was curated by Dr Nick Warr, Lecturer in Art History and Curation at the University of East Anglia, Academic Director of The East Anglian Film Archive and Curator of Photographic Collections (UEA), and Dr Simon Dell.