Applying traditional solutions to make food systems sustainable

WE ARE WHAT WE EAT

Tribal communities in rural India know all about living sustainably. Yet gradual alienation from their environment has meant their voices have become marginalised, their wisdom and knowledge of traditional food lost. Now they are particularly vulnerable to food and nutrition insecurity.

Researchers from UEA are partnering with development organisations and grassroots community groups in India to boost unconventional innovations that improve diet and health in tribal areas. Young people are playing a crucial part, becoming powerful agents of food system transformation, recording and sharing traditional knowledge, and advocating for locally controlled food systems.

The Sustainable Food Systems project is part of UEA's Global Research Translation Award (GRTA), a £1.36 million project to help tackle health, nutrition, education and environment issues in developing countries. The project started in October 2019 and was funded by the UK government’s Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) programme thanks to the Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) international aid budget. The kind of innovative research demonstrated in this project is under threat if cuts to ODA funding are not reversed.

The project team includes researchers from three Indian institutions – PRADAN, KISS, and Gram Vaani - and is coordinated by Prof Nitya Rao from the School of International Development at UEA.

Prof Nitya Rao at University of East Anglia

Prof Nitya Rao at University of East Anglia

Working closely with indigenous communities in two remote tribal areas in Bihar and Odisha states the team are empowering local communities to record their traditional knowledge, and demonstrate that local-scale food systems are a sustainable way to provide dietary diversity and nutritional benefits.

In India, the project is known locally as CHIRAG, which in Hindi means ‘lamp’. CHIRAG stands for ‘Creative Hub for Innovation & Reciprocal research & Action for Gender equality’.

Making films about traditional foods

Film is a valuable tool when it comes to knowledge sharing, giving communities “contextual knowledge and helping them develop a sense of pride in their traditional culture.”

The GRTA project provided cameras and training sessions from UEA filmmakers Christine Cornea and Alex Smith to enable local communities in two tribal locations to create their own films. The training included tips on various aspects of filmmaking, including storyboarding, shooting, and editing.

In the Covid-19 lockdown, many families became more reliant on foraged foods as local markets closed. Screened in local communities and shared online, these films became a valuable resource, with content focusing on foraged foods and traditional crops, showing collection, preparation and cooking techniques and highlighting nutritional benefits. The films are an invaluable part of the digital hub being developed by the project, amplifying learning to other tribal communities through online and audio platforms, and raising awareness to local government offices and education providers. Already they are receiving media attention and government awareness.

“Shooting films on wild forest foods gives the Santhal community contextual knowledge and helps them develop a sense of pride in their traditional culture"

What’s more, the young filmmakers are learning about traditional foods and sustainable agriculture from their elders, whilst simultaneously improving their digital and technology skills.

This film, created by a youth collective from Bihar called the Lahanti Club, profiles Munga Ara, the Santhali name for the Moringa or Drumstick tree. The leaves provide various micronutrients, vitamins, anti-oxidants and fibre. The film is directed by local youth Motilal Hansda, and shows women collecting, processing and cooking the leaves, accompanied by a soundtrack of beautiful singing by Kusum Hansda, a member of Lahanti club.

Tribal youth learn how to make films in Odisha

Tribal youth learn how to make films in Odisha

Alex Smith shows young children in Bihar how to use the camera

Alex Smith shows young children in Bihar how to use the camera

The Lahanti youth club

The Lahanti youth club

Film training session in Odisha with Alex Smith (UEA)

Film training session in Odisha with Alex Smith (UEA)

Women learn how to use cameras and create films

Women learn how to use cameras and create films

Christine and Alex film a women's self help group discussion about sustainable food systems in Bihar

Christine and Alex film a women's self help group discussion about sustainable food systems in Bihar

Christine Cornea shoots footage of a women's self help group in Bihar

Christine Cornea shoots footage of a women's self help group in Bihar

Discussion with youth volunteers from four blocks of Koraput regarding filming on food Systems and festivals

Discussion with youth volunteers from four blocks of Koraput regarding filming on food Systems and festivals

In addition to the villagers’ own films, UEA’s Christine and Alex worked with the two tribal communities to co-produce four professionally edited films for use in policy meetings and online events. Shot in the Koraput district of Odisha state, the film on Mahula flowers profiles the versatility of this wild food, from medicinal purposes to making jams and syrups, for livestock feed, oil and even wine!

The film demonstrates the role women play in collection, processing, marketing and selling. These films document how traditional knowledge and practices safeguard the rich biodiversity of these remote areas, whilst also providing good livelihoods for the people within sustainable limits.

Consultants in the UK and India are conducting nutritional analysis of tribal foods and recipes to provide scientific evidence of the benefits of traditional food systems to legitimise the findings, and are creating recipe books with nutritional information.

“There is a perception among the villagers that we as in villagers cannot produce films or shoot photographs but this perception was broken when I stood in front of them with a camera in my hand and was making films around local foods”

Bhuna katkom is a traditional recipe made up of rice, crab and salt. Analysis found that this recipe met the requirements of macronutrients including carbohydrate, protein, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats. Additionally, it also met the requirements of vitamins such as vitamin E, B2, B3, B5 and B12, and minerals including calcium, zinc, selenium, iodine. In contrast, another recipe analysed Hau ki chatni (red ant chutney) is a dish consisting of red ant, garlic, chilli, ginger, salt and cumin. Analysis showed that Hau ki chatni was low in all nutrients and energy, showing that this would need to be eaten with other foods to meet dietary requirements.

Locally foraged leaves

Locally foraged leaves

Locally foraged pulses

Locally foraged pulses

Red ant chutney ingredients

Red ant chutney ingredients

Using an interactive phone system to collect and share knowledge

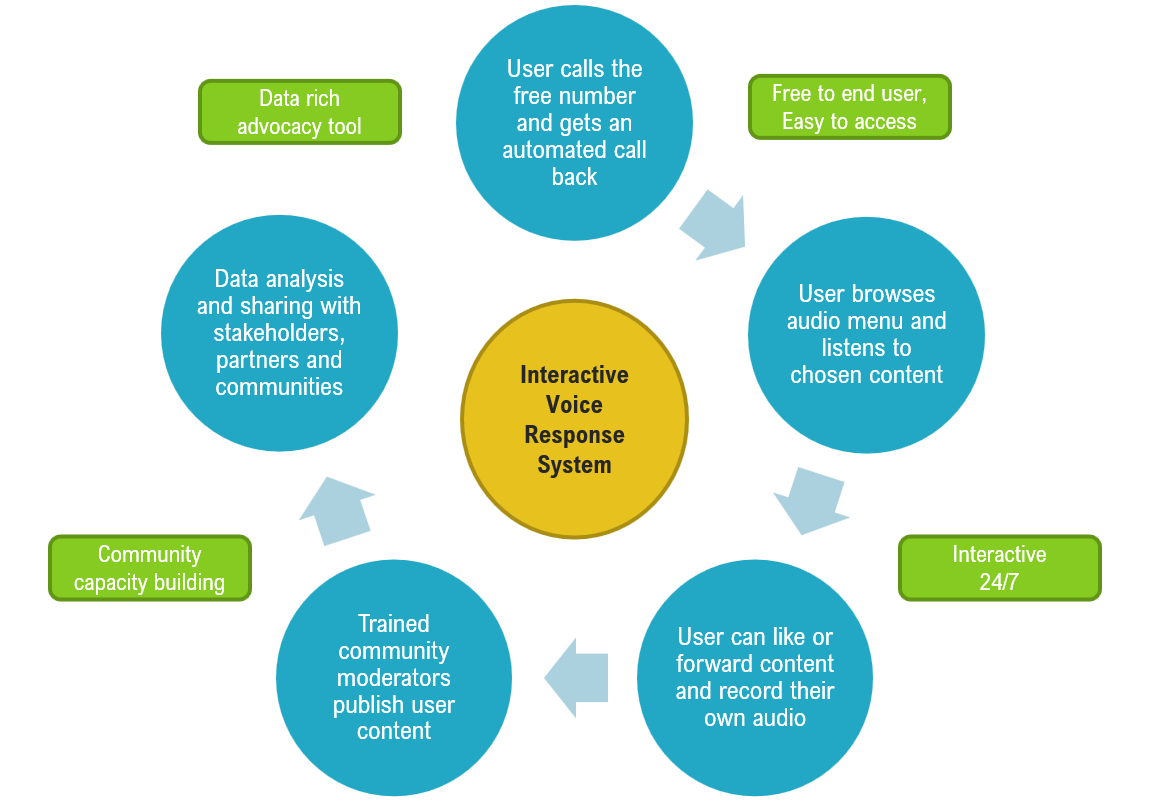

An Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS) is a mobile-based audio platform for social development, where people call a free number and interact with informative content. It is particularly useful in remote rural areas with high levels of illiteracy, and the project has launched an IVRS in both the Bihar/Jharkhand and Odisha research locations.

The system can be used to share studio-generated content, such as podcasts and interviews with experts, and also to collect and share user-generated content from community members, like comments, concerns, recipes, songs, stories. An IVRS is accessible 24 hours a day, seven days a week, through a free phone number with a simple mobile phone handset.

The process (blue) and features (green) of an Interactive Voice Response System.

The process (blue) and features (green) of an Interactive Voice Response System.

The partners have created content about local foods, production techniques, traditional recipes and health and nutrition information, and co-produced content through creative practices like theatre groups, kitchen gardens and participatory films. They run seasonal programmes, for example, summer is known as the hunger period, and during this time people can listen to information about locally available fruits and plants in their forests that have high micronutrients. Community members are encouraged to submit own content about local foods, recipes and indigenous knowledge.

These diverse content types provide a rich resource for community learning and knowledge sharing, bespoke to the local area and from a trusted system moderated by trained volunteers.

Boys in Bihar listen to lessons on the IVRS during lockdown

Boys in Bihar listen to lessons on the IVRS during lockdown

A theatre workshop in Piprasol, Jharkhand

A theatre workshop in Piprasol, Jharkhand

A community group in Odisha listens to the IVRS

A community group in Odisha listens to the IVRS

A woman in Odisha listens to content on the IVRS

A woman in Odisha listens to content on the IVRS

Women from Odisha listen to content on the IVRS

Women from Odisha listen to content on the IVRS

The team have also used IVRS to share information about COVID-19. Migrant workers stranded in different states without access to food, work or accommodation in the first lockdown were able to use the IVRS to seek help and redress grievances. The impact of the pandemic on local markets in Odisha was widely raised on the IVRS and is documented in the film Rural Markets and the Coronavirus Crisis.

“Many listeners shared drying and storing methods, along with the medicinal properties of mango leaves”

A key component of a successful IVRS is recruiting a group of community mentors to become champions and moderators of the system. The project partners provide training to these mentors, helping them to create content, to promote the system amongst their families and friends, and teaching them how to moderate the content items submitted by callers. Young people have become the social infrastructure essential for the system to function effectively and to become self-sustaining.

They took on leadership roles very quickly when the COVID-19 lockdown restricted fieldwork from the project partner teams, even recording audio lessons for children to access through the IVRS whilst schools were closed. These community mentors are paid a stipend through the project for the content they create and the moderation and promotion responsibilities they have.

Children from #Santhal community in #Bihar are listening to creative and contextual educational content through the #CHIRAGVaani community IVR platform. This helps them to continue their learning when schools are closed due to the #pandemic https://t.co/Q7HG1O8yxL

— Gram Vaani (@GramVaani) October 26, 2020

“Project CHIRAG has set the momentum towards reviving the sustainable food systems in Koraput and Kandhamal districts of Odisha. From setting up of the Interactive Voice Response System that provides real-time response on diverse, indigenous knowledge systems to building a cadre of youth who are being trained on documenting indigenous practices relating to food security; Project CHIRAG … has created a repository of indigenous knowledge and practices"

Dr. Achyutananda Samanta, Member of Parliament, Kandhamal Constituency, Odisha State, India

Amplifying indigenous voices beyond the margins

Through the CHIRAG project, people of all ages, genders and trades have discovered how to make their voices heard within their communities and advocate for resilient and equitable food systems. The ODA funding has enabled their voices to be heard regionally, nationally and even globally.

As the research draws to a close, the partners are concentrating efforts on policy meetings with state and national government departments, some of the films have been profiled in an international film competition and findings from the work were included in a Dialogue for the UN Food Systems Summit. A new Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) called Creative Communication, Extension and Community Resource Management for Sustainable Development has been designed to train government officials and development practitioners about equitable and sustainable food systems.

Great to be part of today's @FoodSystems Independent Dialogue: Women’s Agency and Gender Equity in Food Systems with @nityarao63 @TIGR2ESS @TheNISD @FAO @Krishak_Samaj @trinidad1949

— UEA's Global Research Translation Award (@grta_project) June 10, 2021

#FoodSystems pic.twitter.com/NT5NHoSQJr

The GRTA Sustainable Food Systems project focused on two discrete locations in India, but the findings are relevant to countries across the world. Generally, food sources are becoming less diverse and less resilient, with greater reliance on mono-cultures and large companies to process and supply food, leading to nutritional, societal and environmental risk. The pandemic has highlighted the risks associated with long supply chains, suggesting food security across the world could be improved by growing more diverse foods closer to home.

The importance of empowering young people within the food sector is recognised by the Committee on World Food Security in this report HLPE Report 16 and so the lessons learned from remote rural areas of India about paying attention to all voices and respecting traditional and locally contextual knowledge could contribute to sustainable food systems in many other locations, including those closer to home.

The project group

PRADAN Nivedita Narain, Shuvojit Chakraborty, Gautam Bisht, Arundhita Bhanjdeo, Atul Purty, Astha Upadhyay, Ayesha Pattnaik, Sushmita Dutta

KISS (Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences) Suraj Kumar, Shubhasree Shankar, Nizni Hans

Gram Vaani Sayonee Chatterjee

To read blogs and watch films from the Sustainable Food Systems project, please visit our web page or follow us on Twitter @grta_project

The Norwich Institute for Sustainable Development was launched earlier this year with funding from the John Innes Foundation. The NISD harnesses expertise across the Norwich Research Park to enable equitable, food secure and sustainable futures.