The Gloucester:

The sinking of a party boat

It was meant to be a very different kind of voyage.

When James, Duke of York and Albany, set sail for Edinburgh in May 1682, he was in the mood for celebrating.

But when the Gloucester hit a sandbank off the north Norfolk coast in the early hours of the 6 May, the ship was underwater within an hour. The resulting tragedy took the lives of somewhere between 130 and 250 crew and passengers.

It also left an incredible collection of artefacts beneath the waves, offering us, 341 years later, a unique insight into the lives of those on board.

Here, Dr Benjamin Redding, Senior Research Associate and maritime historian at the University of East Anglia, talks us through the fascinating political context of that fateful journey – and how research is helping us piece together the story of a royal celebration that turned to disaster.

'Where the party begins'

“When Charles II returned to England from exile on the continent in 1660, he rejoiced with parties and the theatre, for which he gained the nickname 'The Merry Monarch' and that's exactly what was happening with James in 1682.

"Charles invites him to come back permanently: he's been accepted as the heir to the throne, he's defeated his enemies, this is where the party begins,” Dr Redding explains.

“The Gloucester was, in many respects, a floating court. It was time to celebrate. And the Gloucester’s many artefacts suggest that’s exactly what James was doing.”

James II, by Henri Gascar © Wikimedia Commons

James II, by Henri Gascar © Wikimedia Commons

The Wreck of the Gloucester off Yarmouth, 6 May 1682, by Johan Danckerts © Wikimedia Commons

The Wreck of the Gloucester off Yarmouth, 6 May 1682, by Johan Danckerts © Wikimedia Commons

Charles II of England in Coronation robes, by John Michael Wright © Wikimedia Commons

Charles II of England in Coronation robes, by John Michael Wright © Wikimedia Commons

Charles II dancing at a Ball at Court, by Hieronymus Janssens © Wikimedia Commons

Charles II dancing at a Ball at Court, by Hieronymus Janssens © Wikimedia Commons

Archaeological analysis

Those recovered artefacts include many wine bottles. Julian and Lincoln Barnwell and Tiny Little, the divers who first discovered the wreck and its incredible contents, have rescued 149 bottles from the wreck site so far, including 29 with their airlocks and original liquid still inside.

A selection of wine bottles from the Gloucester wreck © Norfolk Museums Service, Norfolk Historic Shipwrecks Ltd

A selection of wine bottles from the Gloucester wreck © Norfolk Museums Service, Norfolk Historic Shipwrecks Ltd

"It clearly suggests that the passengers weren't just sitting around idly,” Dr Redding laughs.

“What I find particularly interesting about the wine is that we didn't really know anything about its significance to the Gloucester’s story until the Barnwells found the site," says Dr Redding.

"The historical records don't cover wine on the journey, they don't tell us that the passengers were drinking heavily and having a good time. It's the archaeology that has told us that.”

So what does this discovery mean for our understanding of the events of that evening and the fateful morning that followed?

“If people were drinking, perhaps excessively, on the night before the wreck, then when they woke up to the commotion caused by the Gloucester striking the sandbank at 5.30am they would have had little sleep and may still have been intoxicated.

"Would it have affected how well people could swim, especially when many were poor swimmers (as was common at the time)? If alcohol hadn’t been involved, would less people have drowned?

"We can’t answer this question, but it is an interesting one to ask.”

That's entertainment

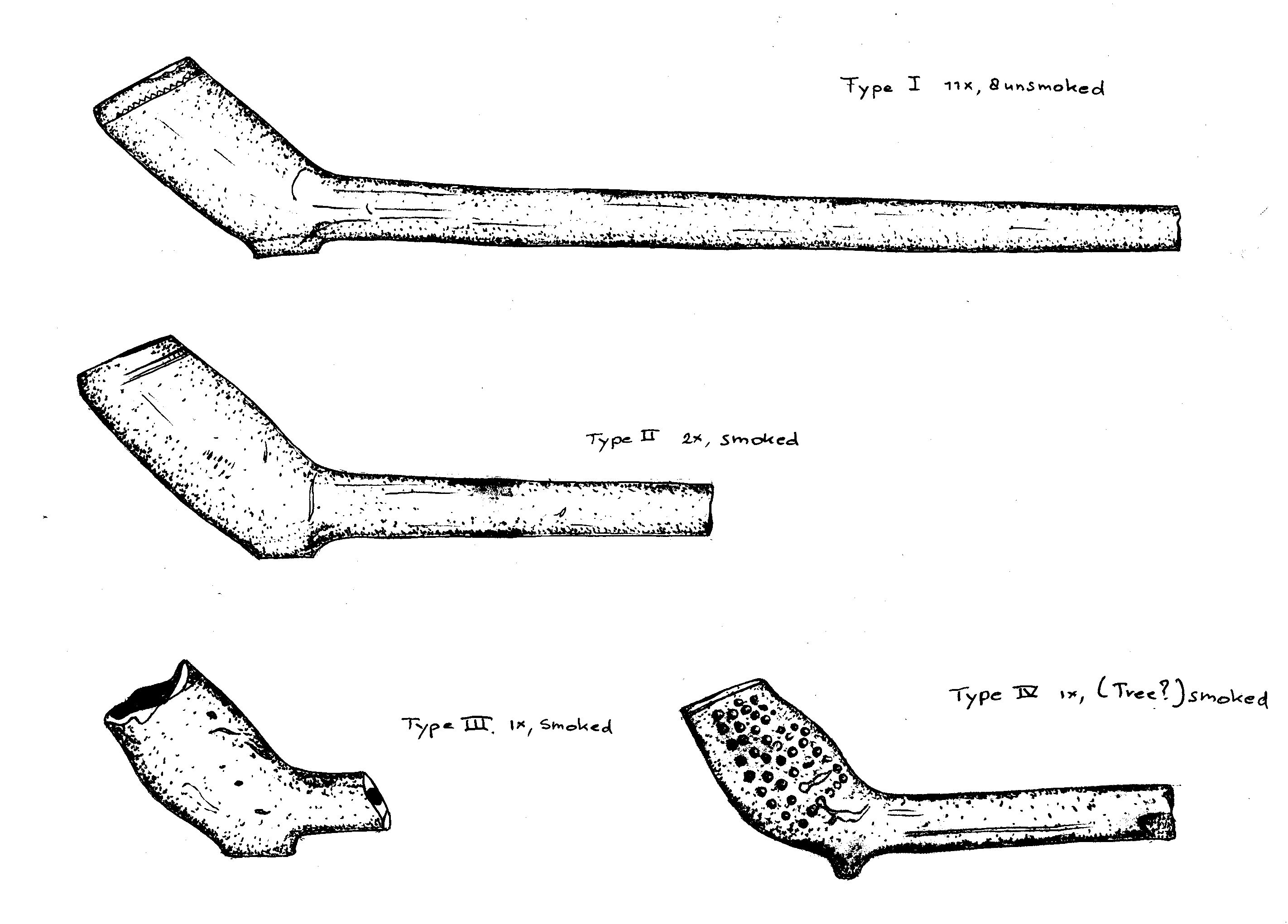

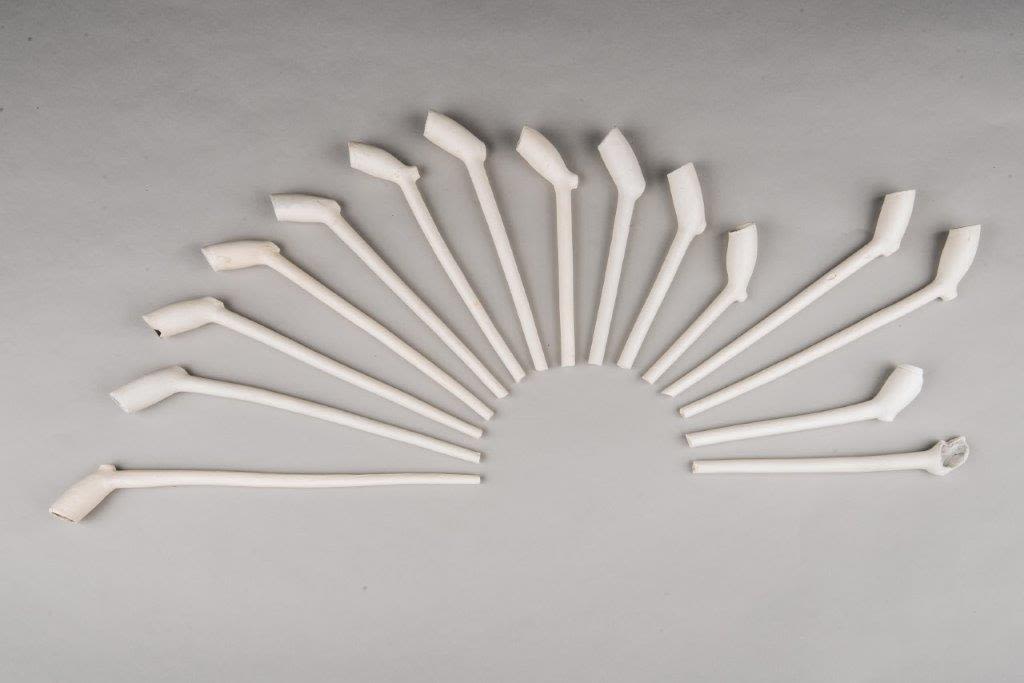

There are other archaeological nods to the jovial mood before the tragedy, Dr Redding continues, including the discovery of many clay pipes for tobacco smoking, and the record of famous musicians on board the ship, such as Thomas Greeting, a renowned flageolet and violin player who was “employed on the Gloucester as part of the king’s private music”, before losing his life that morning.

“James would have had musicians on board because he wanted to be entertained," Dr Redding explains. "And as you’d expect with the Stuart court, there’s going to be music.”

© Norfolk Historic Shipwrecks

© Norfolk Historic Shipwrecks

© Norfolk Museums Service, Norfolk Historic Shipwrecks Ltd

© Norfolk Museums Service, Norfolk Historic Shipwrecks Ltd

'A gentleman's drink'

We don’t have insights into the food served to the passengers on the Gloucester, Dr Redding continues, although records show that the crew would have had “barrels of salted pork and beef, peas, cheese and butter, bread – a very basic kind of diet”.

“But for the passengers, we don’t have the same records, largely because they brought food on board themselves,” he continues. And they would have brought the wine too, which opens up other fascinating questions for historians.

“Wine would very rarely have been drunk by the average seaman at this time,” Dr Redding explains. “They would have drunk beer.

Wine in the 17th Century was not the same as it is today though, he continues, and “probably averaged closer to 5% abv”.

The politics of plonk

Through analysis by biochemist and wine scientist Geoff Taylor, researchers have uncovered some fascinating possibilities for the bottles’ contents and provenance.

“Two of the bottles with liquid contents have been analysed so far and it seems that they have characteristics from different regions: one from a cooler northern European area and one with attributes that are similar to the French environment," Dr Redding continues.

"This fascinates us as historians, because it seems quite possible that the Gloucester’s passengers were drinking French claret.”

There were deep tensions between Protestant England and Catholic France, Dr Redding continues, leading to a ban on the sale and import of French claret in the country since the 1670s, so its potential presence on the Gloucester is significant.

“Wine was highly politicised at this time,” Dr Redding says. “The best wine is associated with France, but France is associated with Catholicism. The English Parliament attempted to prohibit the import of claret, which was the favourite drink of the Stuart court, and there’s no way anyone would have been officially allowed to buy it.

“But we also know that James and his supporters, the pro-Stuart Tory party, would have had a fancy for French claret. And it's quite possible that they had access to it via other, unofficial routes. In effect, there was one rule for them and another for everyone else.”

Explore more:

- Visit the exhibition: The Last Voyage of the Gloucester: Norfolk’s Royal Shipwreck, 1682

- The background of The Gloucester

- The Last Voyage of the Gloucester (1682): The Politics of a Royal Shipwreck (journal article)

_ Uncovering the Gloucester shipwreck (YouTube)

Bellarmine bottles recovered from the Gloucester © Norfolk Museums Service, Norfolk Historic Shipwrecks Ltd

Bellarmine bottles recovered from the Gloucester © Norfolk Museums Service, Norfolk Historic Shipwrecks Ltd

Wine bottle with cork © Norfolk Museums Service, Norfolk Historic Shipwrecks Ltd

Wine bottle with cork © Norfolk Museums Service, Norfolk Historic Shipwrecks Ltd