Thinking like mountains - narrating the climate crisiS

UEA staff, students and alumni recommend art to help us comprehend the climate crisis

Thinking Like Mountains - Narrating the Climate Crisis was a panel discussion that bought together writers, activists and thinkers to discuss the role of the arts in communicating and reimagining the greatest challenge of our time: the climate emergency. What new stories can mark out the path before us?

Dramatist and UEA Professor of Scriptwriting Steve Waters was joined by author and environmental historian Jessica J. Lee and environmental activist and academic Joycelyn Longdon on 22 June at the Royal Institution in London and online.

In this blog, UEA researchers, students and alumni recommend other artworks, books, films, and music that can help us to understand the scale of the climate crisis, promote positive action and support those of us who are suffering from climate anxiety.

TESSA MCWATT

Writer and Professor of Creative Writing

Sometimes to think of art in an emergency seems like a frivolity, like foolishness or distraction while the world burns. But this crisis is also one of the heart, of grief, and our greatest imaginative powers are the only things that might in the end rescue us.

There a few pieces of art that have touched me deeply and inspired me to keep up the resistance, because the issue is a political one, and it demands solidarity; it demands hope. Two stunning sculptures that demonstrate the consciousness of climate grief are by indigenous artists - Abraham Anghik Ruben and Floyd Kuptana - who have interpreted the crisis through traditional soapstone sculptures that now bear the weight of climate destruction and represent the community's grief. And reading remains crucial. One of the books I've turned to recently has been Amitav Ghosh's The Nutmeg's Curse - a beautifully written indictment of colonialism as a root cause of the planet in crisis.

Another book is by the founder and director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment, Robin Wall Kimmerer, called Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants. We need indigenous wisdom to get us through.

Tessa McWatt’s latest novel The Snow Line is out now, published by Scribe. You can read more about Tessa’s work on the CreativeUEA website. You can see more of Abraham Anghik Ruben’s work on the Kipling Gallery website.

Life out of Balance by Abraham Anghik Ruben. Image: Daniel Dabrowski/Kipling Gallery

Life out of Balance by Abraham Anghik Ruben. Image: Daniel Dabrowski/Kipling Gallery

Arctic Apocalypse by Abraham Anghik Ruben. Image: Daniel Dabrowski/Kipling Gallery

Arctic Apocalypse by Abraham Anghik Ruben. Image: Daniel Dabrowski/Kipling Gallery

ALAN FINLAYSON

Professor of Political & Social Theory

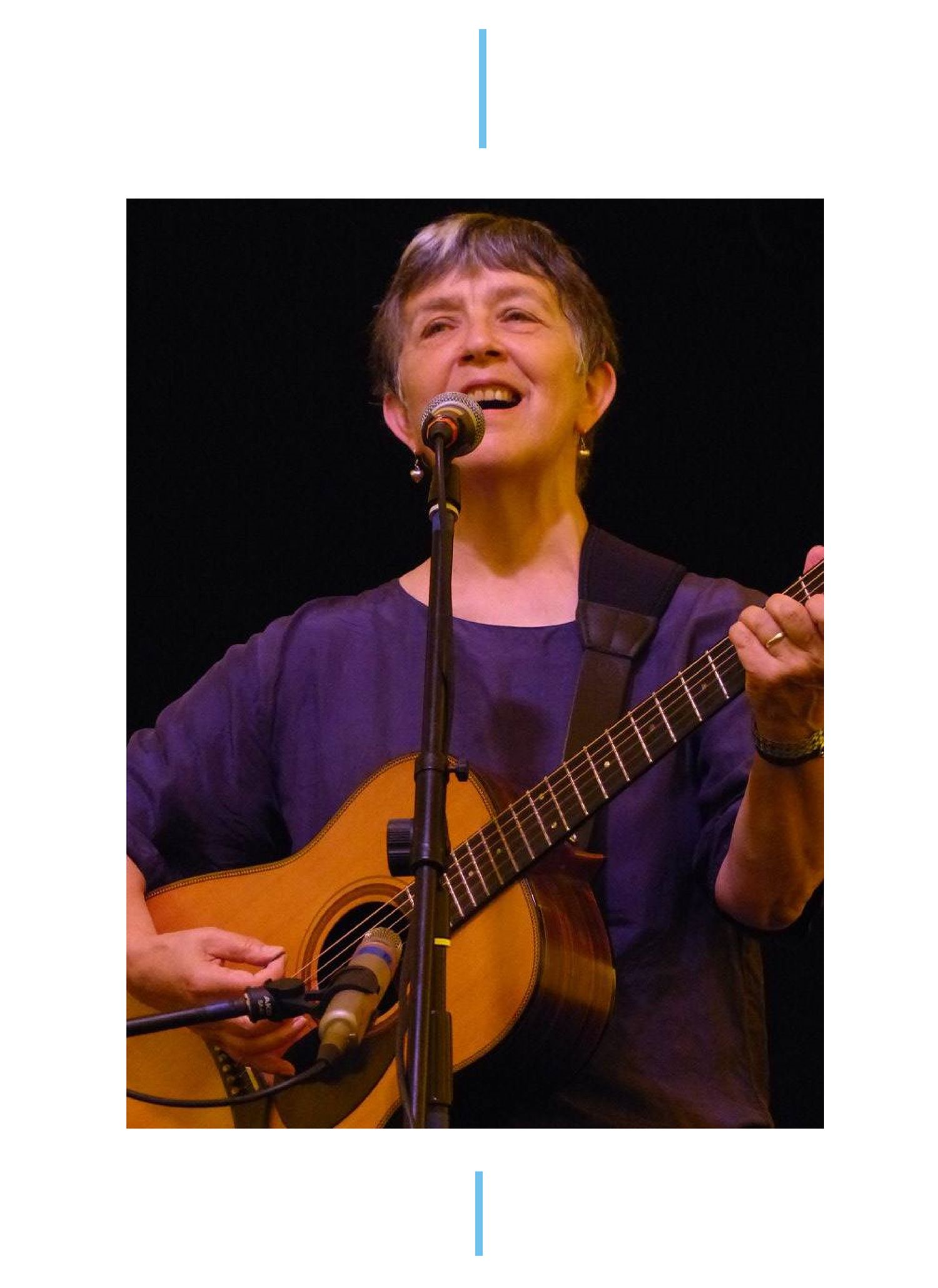

As part of a research project concerning the history of English protest songs I’ve had the opportunity to think a lot about Maggie Holland’s song A Place Called England, and also to interview her about it. The song isn’t specifically about climate change, and its focus on one nation might seem at odds with the global responsibility to reduce emissions. But the song is about people taking responsibility for the land they live on, and doing so with an understanding of both its past and its future. At the start of the song – echoing a long musical tradition – Holland imagines herself ‘like a hero in a song’ looking for the past of her childhood, buried now under thoughtless ‘development’. But from the window of a train, she sees back-gardens and allotments, well cared-for and nurtured, bursts of colour and fruitfulness amongst the gloom.

Maggie Holland at Shrewsbury festival, 2016. Image: Jeremy Searle

Maggie Holland at Shrewsbury festival, 2016. Image: Jeremy Searle

Namechecking English heroes both mythical (St. George and King Arthur) and real (Daniel, better known in 1990s England as ‘Swampy’, and for his direct-action protests against road building and airport expansion), Holland reminds us that a country is not an abstract political or economic idea. Instead, it is a place, of ‘limestone gorge and granite fell’ and that such places endure, not least because the people who live upon them take their time to care about them and work with, not against them. Perhaps Holland’s ‘crazy diggers’ seem too small to address the enormity of climate change. But Holland’s optimism is not naïve. By the song's end she is looking to the future and simply reminding us that politics – contrary to its media appearance - consists of the countless, because mostly unmeasured, actions of millions, and of their ability to perceive their common interest, to press and to act on their collective interests in deed as well as word. She reminds us too that all politics has a history, that we have been here before, and that the hour always comes around again.

You can visit Our Subversive Voice for more about the history of protest songs. Alan was also involved in Project Change, a programme of climate-change workshops, resources, and competitions led by UEA students and researchers last year. To read more about Maggie Holland and hear her music, visit her website.

JOS SMITH

Poet and Associate Professor in Contemporary Literature

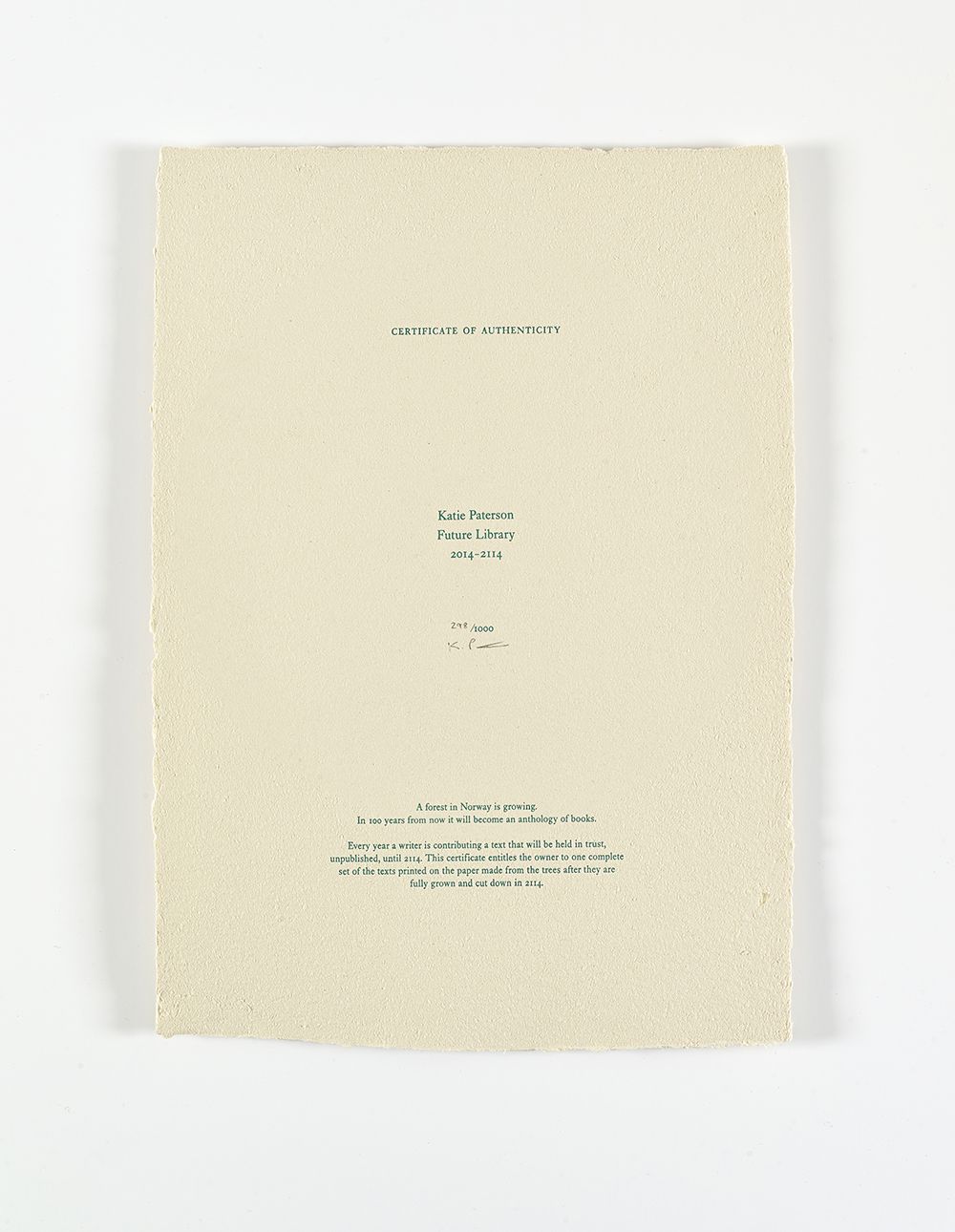

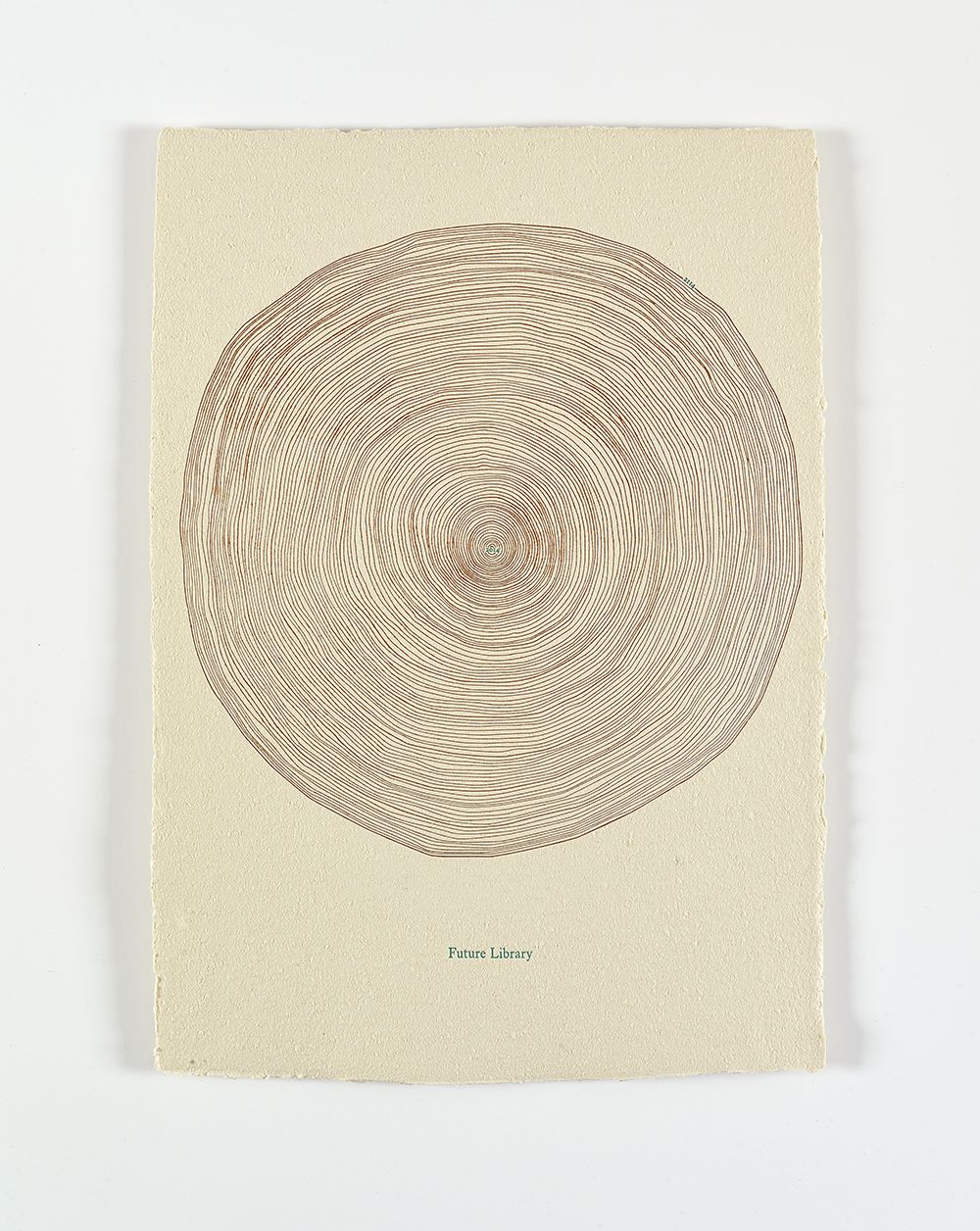

In 2014, British conceptual artist Katie Paterson created Future Library, a work of art that saw a forest of 1,000 Norwegian spruce planted in Nordmarka, north of Oslo. Each year, until 2114, an author is invited to write a new work of literature that will only be published when the forest has reached maturity, and that will be printed on paper made from the planted trees. There will be 100 books in total by the time the artwork is complete. So far, the authors include Margaret Atwood, David Mitchell and Han Kang, whose books will go unread during their lifetime, greeting a generation of readers who are largely yet to be born. Given that the artwork will likely outlive the artist, Paterson has instituted a ‘Future Library Trust’ whose role it is to select and invite the authors and ‘compassionately sustain’ the forest over the century ahead.

Today, just when we need to be thinking of the long game, time can feel uneasily contracted, from workplace pressure and stress to political short-termism to the rolling crises of the 24-hour news cycle. Future Library opens up a refreshingly deep sense of the future in a very tangible way. We are drawn to reflect on the slow growth of the trees, season after season, year after year, synthesising new material all the time in the flesh of their heartwood. And we are drawn to reflect on the gradual accrual of cultural value as book after book is written and deposited into the safeguarded archive. What is growing there is a rare gift for future generations. But we can experience that investment and care for the future as a gift too, one that can lift our attention out of the acute anxieties of the present towards a hope founded on longer ambitions and grounded responsibilities.

SUN is Jos Smith’s latest pamphlet of poetry and follows his 2016 debut collection, Subterranea. To find out more about this artwork, visit the Future Library website. In 2021 it was announced that Tsitsi Dangarembga, UEA’s International Chair of Creative Writing, will become the eighth author to contribute to the Future Library project.

Future Library certificates by Katie Paterson. Image: John McKenzie

Future Library certificates by Katie Paterson. Image: John McKenzie

Future Library certificates by Katie Paterson. Image: John McKenzie

Future Library certificates by Katie Paterson. Image: John McKenzie

JON CONRADI

Founder of Mosaic and UEA graduate

I don’t understand the scale of the problem, I don’t think it is understandable. Just one lost species is an unknowable loss. These are some artworks of various forms that have helped me to at least get some sense of the scale and inspire action.

Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson: An impressive sci-fi book that sketches out in detail a possible path. Terrifying but hopeful. Inspires different types of action and shows how distinctly separate pieces could fit together to drive change.

The Green Planet: David Attenborough and his documentaries have the power to reach out and respark joy and wonder in the life all around us. This is a first step for so many.

Leviathan by Philip Hoare A beautiful exploration of whales, and our relationship with them. Helps bring to life not just these incredible mysterious animals but how close we came to wiping them out over a century ago.

MODPO - A free public course on American Poetry: Not about climate change. But hopeful, inspiring and an accessible way to discover and delve into the power of poetry. A beautiful way to re-see possibilities and our creative potential. Or at least find new threads to start to stitch together.

PROF SARAH BARROW

Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Arts and Humanities

The concept of Buen Vivir (literally meaning ‘good living’ but more broadly referring to a framework for living in a way that prioritises respect for all life) is fundamental to the thousands of communities living in the Amazon where threats to food and water security are a tragic part of daily life, greatly affected by man-made climate change.

In The Forest Something Stirred is an online exhibition featuring two new works of digital art, Treeline by Ruth Maclennan and Natural Error by Rodell Warner. Each focus on the flora and fauna of our natural landscape, and how it is being marked by climate change. Created to coincide with COP26, the two works highlight the precarity of species in the face of the decimation of the environment and the loss of biodiversity.

Jointly commissioned by Film and Video Umbrella and Forestry England, Treeline was created following a public callout for audio and video material. Artist Maclennan received footage from across the world, including contributions from two of the young women, Karen Pamela Huere Cristobal and Maricielo Gonzales, who participated in the British Academy funded project Women of Influence: Exploring the potential and impact of indigenous female community participation and leadership in Peru. As Maclennan writes: "Treeline’s depiction of an endless landscape invites us to reflect on the interconnectedness of our planetary ecosystems while each individual clip underlines the unique qualities, characteristics and threats faced in the locations where filming has taken place."

Still from Treeline (2021) by Ruth Maclennan. Jointly commissioned by Film and Video Umbrella and Forestry England. Supported by John Hansard Gallery and Hunterian, University of Glasgow.

Still from Treeline (2021) by Ruth Maclennan. Jointly commissioned by Film and Video Umbrella and Forestry England. Supported by John Hansard Gallery and Hunterian, University of Glasgow.

Visit the In The Forest Something Stirred website to see the two commissions, Treeline by Ruth Maclennan and Natural Error by Rodell Warner. The two works highlight the precarity of species in the face of the decimation of the environment and the loss of biodiversity.

STEVE WATERS

Dramatist and UEA Professor of Scriptwriting

One challenge of the climate crisis is its unprecedented nature. Most of the things we grapple with have all too many precedents evident in the art of the past. The assault on Ukraine can be understood through War and Peace; the rise of the populism, well, Richard III has that covered. But the climate emergency has such reach and depth it’s hard to find stories that help us navigate it.

I’ve recently re-worked a play that feels truer now than when it was first staged in the 1880s. Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People is surely the first ecological drama. If you’ve never seen it, its premise will feel eerily familiar – a small-town Mayor disavows a lethal threat so as not to forego tourist revenue. OK, we’ve all seen Jaws. But in Ibsen’s tragi-comedy, the threat is toxic water feeding a public bath, not sharks, and it's hunted down by the mayor’s brother, Dr Stockmann, without the aid of a harpoon.

Carbon emissions is a pollution of a different magnitude than this, but the play’s debates are still starkly pertinent: science trumped by vested interests, a whistle-blower ostracised by his community, the short term winning over the long term. Yet Stockmann adds insult to injury with his lofty contempt for democracy, his misplaced confidence that delivering the facts is sufficient to effect change.

Ibsen imagined the dilemma of telling inconvenient truths decades ahead of our polarised times. Even in the 1880s it seemed we’d "had enough of experts". Even then, we felt impelled to shoot the messenger. Yet the play closes with a bracing image of the doctor alone and still fighting; and for all his flaws, his courage seems as necessary to our moment as to Ibsen’s.

The Lasdun Lecture, Thinking Like Mountains - Narrating the Climate Crisis, was on Thursday 22 June 2023 at The Royal Institution in London and online.

Watch the full event here.

TREVOR DAVIES

Emeritus Professor, School of Environmental Sciences and former Director of Climatic Research Unit

Gennadiy Ivanov is a Norwich-based artist who has been in a close art-science collaboration – focused on climate change - with John Pomeroy, who is Director of Global Water Futures (GWF) which is headquartered at the University of Saskatchewan, and me, for the last three years. In the collaboration, which is called Transitions, Ivanov and scientists have worked together closely in the field, in the research laboratory, and in the studio to produce more than 150 pieces of art which have been shown around the UK and in Canada.

Much of the focus has been on the cold regions (high Northern latitudes and elevations), but Ivanov has also painted the impacts of climate change in Norfolk; and a major public art-science project with a strong local focus is currently underway in cooperation with UEA’s Climatic Research Unit. The aims of Transitions are to reach new audiences through art and to raise awareness of the impacts of, and challenges posed by, climate change. It also aims to engender spirits of optimism and resolve in how we may face up to these challenges.

Requiem for Peyto by Gennadiy Ivanov. "Here I am below the current snout of the Peyto Glacier, amidst the new and barren landscape revealed by the glacier’s rapid retreat. Modelling by the scientists shows that the glacier could have almost completely vanished by the end of the decade."

Requiem for Peyto by Gennadiy Ivanov. "Here I am below the current snout of the Peyto Glacier, amidst the new and barren landscape revealed by the glacier’s rapid retreat. Modelling by the scientists shows that the glacier could have almost completely vanished by the end of the decade."

Some of the paintings incorporate images of solutions. The captions which go with the paintings are important vehicles in this regard, but it is the paintings themselves which draw people – especially young people – into the captions and discussions with scientists. Ivanov uses his impressionistic, surrealistic, and allegorical styles to raise eyebrows – and interest – persuading people to want to engage: what is this about? An example of this is the large oil painting Requiem for Peyto. The Peyto Glacier is named after “Wild Bill Peyto” and is located in Banff National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site and Canada’s first National Park. Peyto Glacier has the longest record of any glacier in the world for detailed scientific investigation and has lost more than 70% of its volume since the beginning of the 20th Century.

A common response to this painting is consternation at the rapid decline of one of the iconic features of the Canadian landscape, and an enthusiasm to engage in a discussion of how a rapid mobilisation of effort might yet succeed in avoiding the worst consequences of climate change.

Visit Gennadiy Ivanov’s website for more information about his work, including Transitions. UEA’s Climatic Research Unit (CRU) turned 50 in 2022.

KIT MARIE RACKLEY

Educator, Author, Presenter and Trainer

In 2020 I wrote a piece of performance poetry inspired by the positive actions of young people. Titled Why Not Now?, I wanted to echo and amplify youth voice, and give examples of how they are turning their climate anxiety into climate agency.

Another piece of climate poetry I love is a performance piece by Prince Ea called Sorry. I like to think of it as the sentiment that older generations with power privilege should be saying to the young people of today.

Why Not Now? by Kit Marie Rackley

Why Not Now? by Kit Marie Rackley

You can find out more about Kit Marie Rackley’s work, including Why Not Now, on their website.

The Lasdun Lecture, Thinking Like Mountains - Narrating the Climate Crisis, was on Thursday 22 June 2023 at The Royal Institution in London and online.

Watch the full event here.

CreativeUEA is an interdisciplinary research theme at the University of East Anglia which builds on a longstanding history of creativity and innovation. Find out more at CreativeUEA