WG Sebald at the University of East Anglia

A VIEW BETWEEN THRESHOLDS

“Things outlast us, they know more about us than we know about them: they carry the experience they have had with us inside them and are—in fact—the book of our history opened before us” - WG Sebald, Unrecounted

In June 2024, an event organised in partnership with the National Centre of Writing in Norwich celebrated the recent publication of Shadows of Reality: A Catalogue of W.G. Sebald’s Photographic Materials, and what would have been Sebald’s 80th birthday.

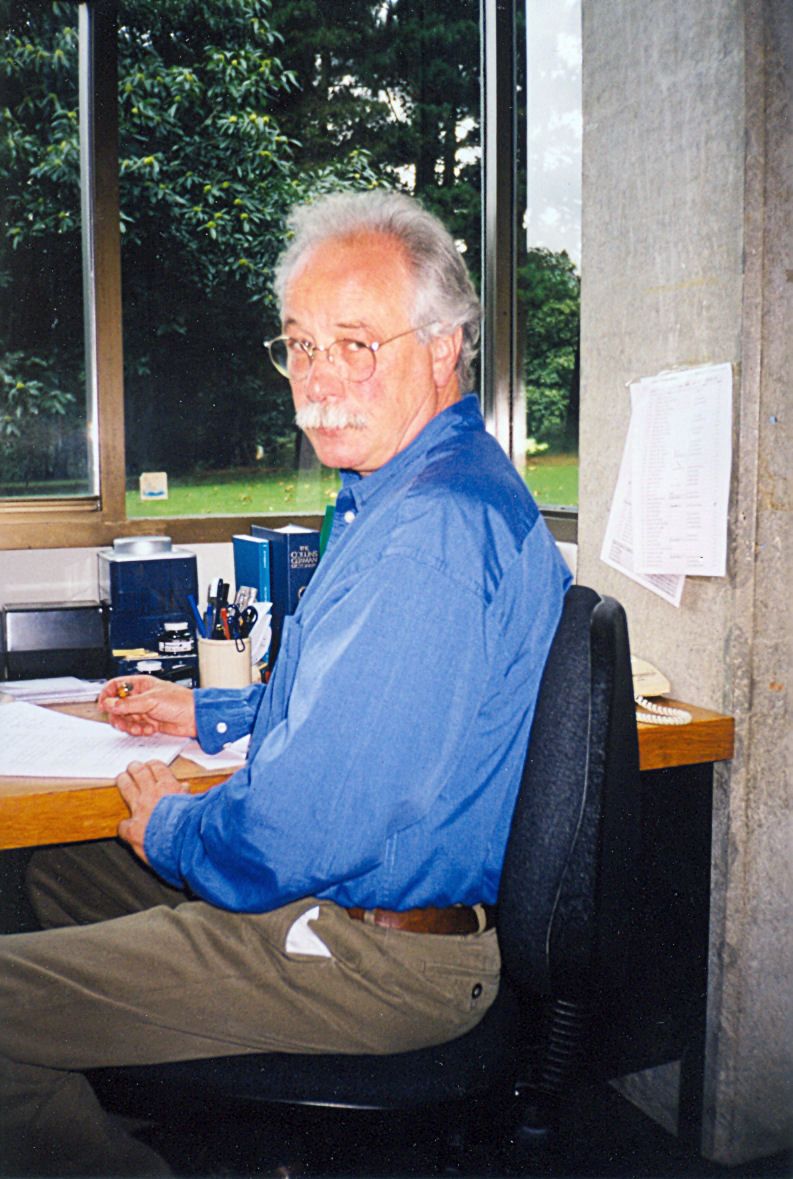

Max, as he was known to his friends and colleagues, taught at UEA for thirty years, and established the British Centre for Literary Translation in 1989.

Now known the world over for books including Austerlitz, The Emigrants, and the Rings of Saturn (the 'most peculiar of East Anglian travelogues'), and once considered a possible recipient of a Nobel Prize, his story, one of dichotomy, of interdisciplinarity, reflects that of the East Anglian university at which he taught.

Dr Nick Warr, Lecturer in Art History and Curation at School of Art, Media and American Studies, delves into his legacy.

"The interdisciplinary nature of Sebald’s work is an oblique portrait of UEA"

WG Sebald is arguably one of the most celebrated writers to have studied and taught at the University of East Anglia. But on a campus defined by the solidity of its building material you’ll find no concrete memorial to him here.

There is no blue plaque for literary pilgrims to gesture to in their social media posts. No building bears a carved inscription for the Virginia Creeper to find purchase. A commemorative copper beech has been rendered indistinct among George Borrow’s ‘umbrageous trees’ that prosper about the University’s parklands. There is one small room set aside at the end of Lasdun and Feilden’s brutalist multi-storey teaching block, but even those who use ARTS 01.06 regularly are perhaps unaware of who the ‘Max’ is that this space has been set aside for.

A puzzle to many visitors, this reluctance to memorialise him comes not from an institutional indifference to his legacy but a collective reticence to give his absence a definite form. A classroom is a space defined by potential and one such possibility is that Max Sebald, back from one of his eccentric sabbaticals, will perhaps just wander back in, his Labrador waddling close behind. This reluctance to conclude the story of Sebald’s time at the UEA comes not just from the sudden and unexpected nature of his death in 2001 but also from the strange potency of the circuitous narratives he left behind in his published work.

"This reluctance to memorialise him comes not from an institutional indifference to his legacy but a collective reticence to give his absence a definite form"

From After Nature (1988) to the posthumously published Unrecounted (2003), ends are perpetually intertwined within beginnings, straight paths reveal themselves to be mazes, and final words invitations to start again. Then there are the photographs that punctuate his prose. The cultural critic Walter Benjamin, a framed poster of whom Sebald fixed to the wall outside of his office, once described the work of the great French photographer Eugène Atget as having the appearance of crime scene photographs because they document absence. The photographs in Sebald’s work share a familial likeness to Atget’s, as they also appear to be clues to a mystery that has yet to reveal itself.

The emigrant

Sebald died twenty years ago this December of a heart attack whilst driving his car to his rural home in Poringland, south-east of Norwich, where he had lived with his family for almost 25 years. He was 57 years old.

Sebald first moved to East Anglia in 1970 when he was appointed Assistant Lecturer in German Language and Literature at the fledgling University of East Anglia. He had previously lived in Manchester, where he was an assistant language teacher at the university. In the late 1960s Manchester was a city still struggling to recover from its war time destruction, its centre a patchwork of soot greyed buildings and rubble strewn vacant lots. For someone who grew up in a small rural community in Bavaria surrounded by green forests and white mountains, living in Manchester, a place blackened by the horrors of industrialisation, was a disorientating but transformative experience. Aspects of his time in Manchester and his move to Norfolk form the basis of his first concerted efforts to consolidate his personal experiences into prose. Started in the mid-1980s these stories would eventually be published as part of The Emigrants in 1992.

It is a common misconception that Sebald turned to fiction late in his career but from his first years at the UEA Sebald continued with the many different forms of writing with which he had experimented as a youth. In parallel to his academic work in England, Sebald wrote poetry, a travelogue, radio scripts and teleplays as well as regularly contributing reviews and articles to newspapers and magazines. Whilst some of the more creatively ambitious projects remained unrealised during his lifetime, what they shared with those that did find an audience was the geographical distance they resolutely maintained between the author and readers.

The British Centre for Literary Translation at UEA was founded by Sebald in 1989

Sebald’s literary reputation stems primarily from the English language reception of his work but almost all of it was written and published in German. With the exception of some academic reviews that he contributed to the UEA’s newly founded Journal of European Studies in the early 1970s, Sebald remained resolutely a writer of the German language though not necessarily a German writer. Today Sebald is a writer predominately read in translation. What we see, or at least what we think we see, is an image of the author through the prism of another language. Until recently, Sebald’s reputation in Germany had little in common with that quickly formed in England and America after the English translation of The Emigrants in 1996.

Soon after registering as a PhD student at UEA, perhaps buoyed by the new institution’s interdisciplinary ambitions and the apparent robustness of its concrete ramparts, Sebald set about cultivating a level of notoriety abroad.

He did so by writing numerous astringent attacks on German literary culture. Specifically, how contemporary criticism sought to negate the fascistic character of certain lauded writers so that National Socialism could be understood as an aberration from rather than a product of German culture. Obviously, upon publication such provocations meant that Sebald did not ingratiate himself with those that presided over Germany’s and Austria’s literary institutions and so found himself excluded from their valorisation. However, Sebald was not without his supporters in Germany, particularly from those who recognized the critical value of this émigré’s double perspective.

The view from WG Sebald's office today

The view from WG Sebald's office today

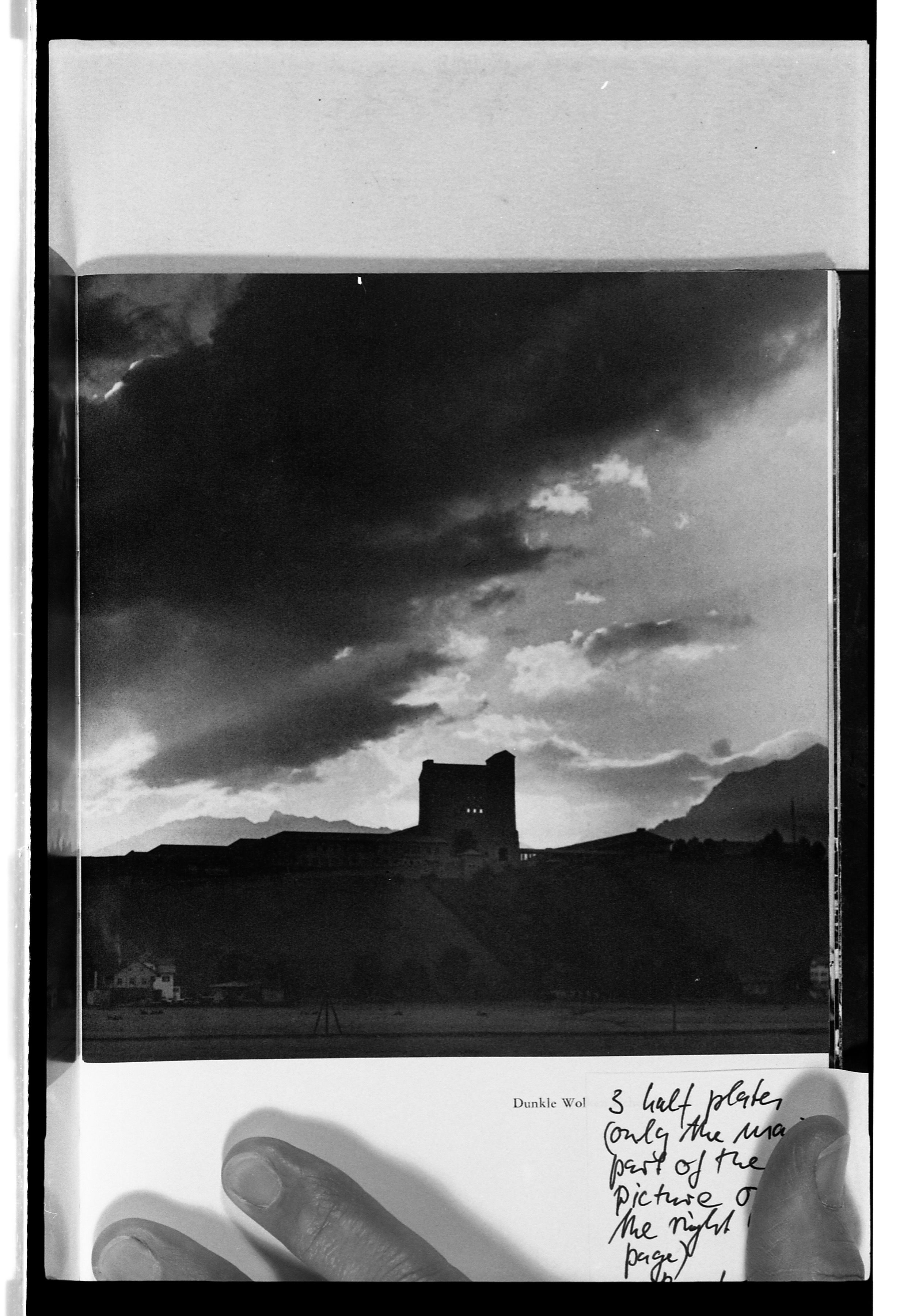

Work in progress: Michael Brandon-Jones preparing an image for Sebald’s Luftkreig und Literatur (UEA, 1998)

Work in progress: Michael Brandon-Jones preparing an image for Sebald’s Luftkreig und Literatur (UEA, 1998)

St Martin's church in Shotesham

St Martin's church in Shotesham

St Mary's church in Shotesham, seen across a field

St Mary's church in Shotesham, seen across a field

The Doppelgänger

There is a wonderful film of Sebald at home in Poringland made for German television in 1990, Sebald’s own VHS copy of which is it the UEA’s British Archive for Contemporary Writing. It shows Sebald in his garden, bouncing on the balls of his feet, enthusiastically discussing the failings of contemporary German literature, though he admits to being ‘fairly new to the business’. The scene then cuts away to shots of his desk with its neat assemblage of papers and photographs and a strategically placed copy of Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida. As the camera pans around the tastefully decorated Georgian study you glimpse through the window Sebald and his wife Ute drinking tea in the garden.

The Englishness of this scene augments a previous sequence filmed a few miles from Sebald’s home. Sebald is pictured approaching the gate of St. Mary’s church in the Norfolk village of Shotesham. He lifts the latch and strides up the rose bordered path towards a wooden bench. Seated, arms stretched across the weather greyed back rest, Sebald surveys the overgrown churchyard and the fields beyond. The gravestones, barely visible in a sea of late summer grass, recede towards a perfectly level horizon. ‘Among his favourite places’, states the commentary in German, ‘the peace and calm, wild nature and open landscape of the area. Born in the Allgäu, he now shudders at the thought of the menacing mountains that he grew up with.’

"The creative freedom that Sebald found in performing, the paradoxical empowering of the self by being somebody else is clear"

A curious rural parish, Shotesham has four medieval churches and visible from the grounds of St Mary’s is the ruined tower of St Martin. It makes a strange picture for those on the road that passes the two towers, St Mary’s and her derelict twin, the past and the present, converging, aligning and then diverging as the traveller circumvents the isolated plot. I’m sure for the future author of The Rings of Saturn, the most peculiar of East Anglian travelogues, the uncanniness of this landscape would not have gone unnoticed, and it certainly didn’t escape the attention of the film makers.

We next see Sebald nonchalantly leaning against a thin metal handrail on a perilously narrow snow-covered bridge that leads across a steep banked mountain stream to another church. Dressed in a heavy coat with the collars turned up against the Bavarian winter, one hand deep in his trouser pocket, the camera slowly zooms in on the author reading aloud from the concluding section of his book Vertigo. The passage recounts the narrator’s imaginary and physical return to the remote Alpine village of his birth, a place, Sebald declaims, ‘more remote from me than any other place I could conceive of.’

The Doppelgänger, the living double, is an idea that pervades Sebald’s work, and this doubling is something that the visual contrast between the two sequences of the film’s montage deliberately alludes to. Made at the time of German reunification, there is no parallel attempt by the filmmakers to unify this double aspect of Sebald’s persona.

As a student at the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg, Sebald was keenly involved in the student magazine often contributing small prose pieces and poems. He was also an earnest member of the university’s drama group. Many of the images of Sebald from this period are photographs of him in costume on stage or theatrically gesturing with script in hand. The creative freedom that Sebald found in performing, the paradoxical empowering of the self by being somebody else is clear in these photographs. So perhaps trying to find the ‘real’ Sebald somewhere between Wertach and Poringland is a futile endeavour. Like the church towers in Shotesham, the congruity between the two Sebalds is a matter of distance and perspective.

The legacy

I started by saying that there is no concrete memorial for Sebald at UEA but, as the fascinating archive of Sebald material held by the BACW attests, traces of his presence do remain about the campus, carefully preserved in its catalogued collections. However, there remains a sense that, like the overlooked objects chanced upon in Sebald’s stories that yoke the past to present, there are items still waiting to be discovered. Things folded into the fabric of the university over time, waiting patiently to announce their continued existence – and I speak from experience.

When I started working as the Curator of Photographic Collections at the University in the Autumn of 2004, my first job was to unpack the thousands of photographs that had been boxed up in large green plastic crates and removed from the Art History department in the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, in preparation for the building’s refurbishment. Sorting through and moving the collection was a laborious and challenging process that took over three years, and to this day I am still discovering items that have doggedly retained their identification stickers from that unsettled period.

3/5 Sebald’s curious photographic practice & the story of his work in our #ArtHistory darkroom @SainsburyCentre @uniofeastanglia is catalogued in “Shadows of Reality” Ed @thenichtwahr & Prof Clive Scott @bhousepress (published later this year) @DLAMarbach https://t.co/gywRr21B2p pic.twitter.com/MpktcUBwoF

— Art History and World Art Studies UEA (@ART_UEA) July 22, 2020

Among the Collection’s numerous red archive boxes was a small Ilford photographic paper box with ‘Sebald’ written faintly in pencil on one side. The box contained a variety of black and white photographs and a few handwritten notes. This was far from unusual, as the department houses an extensive archive of teaching and research materials including reproductions from books for teaching and academic publications. The demands of working in a busy faculty meant that this box sat unscrutinised on a shelf in the archive for some time, until, a few years later I was, by chance, introduced to Clive Scott, Professor of European Literature, at an end-of-term party. During a discussion about photography, I mentioned the ‘Sebald box’ I had found in the collection and suggested he, as a friend of Max’s, might like to come and look at it.

"Go to the second or third floor of the library... you may just find the beginning of another Sebald story ready to be pieced together"

It was not until after another fortuitous meeting outside my office in the summer of 2008 that Clive and I arranged to go through the photographs. As we looked through the box’s contents it became apparent that, rather than reproductions, they were the original prints made for Sebald’s books. The notes left in the box were written by Michael Brandon-Jones, the photographer based in the Art History department, whose old office in the Sainsbury Centre I now occupy.

Decoding the reference numbers and cryptic abbreviations of these informal jottings was difficult and time-consuming but doing so enabled me to locate numerous other Sebald documents from the collection, and most significantly the 35mm film negatives that Michael had made in collaboration with Sebald for all his published work. These negatives had been carefully filed away in the collection among the thousands of others made by students and staff and would have remained there, unidentified, if it weren’t for the serendipitous encounters related here.

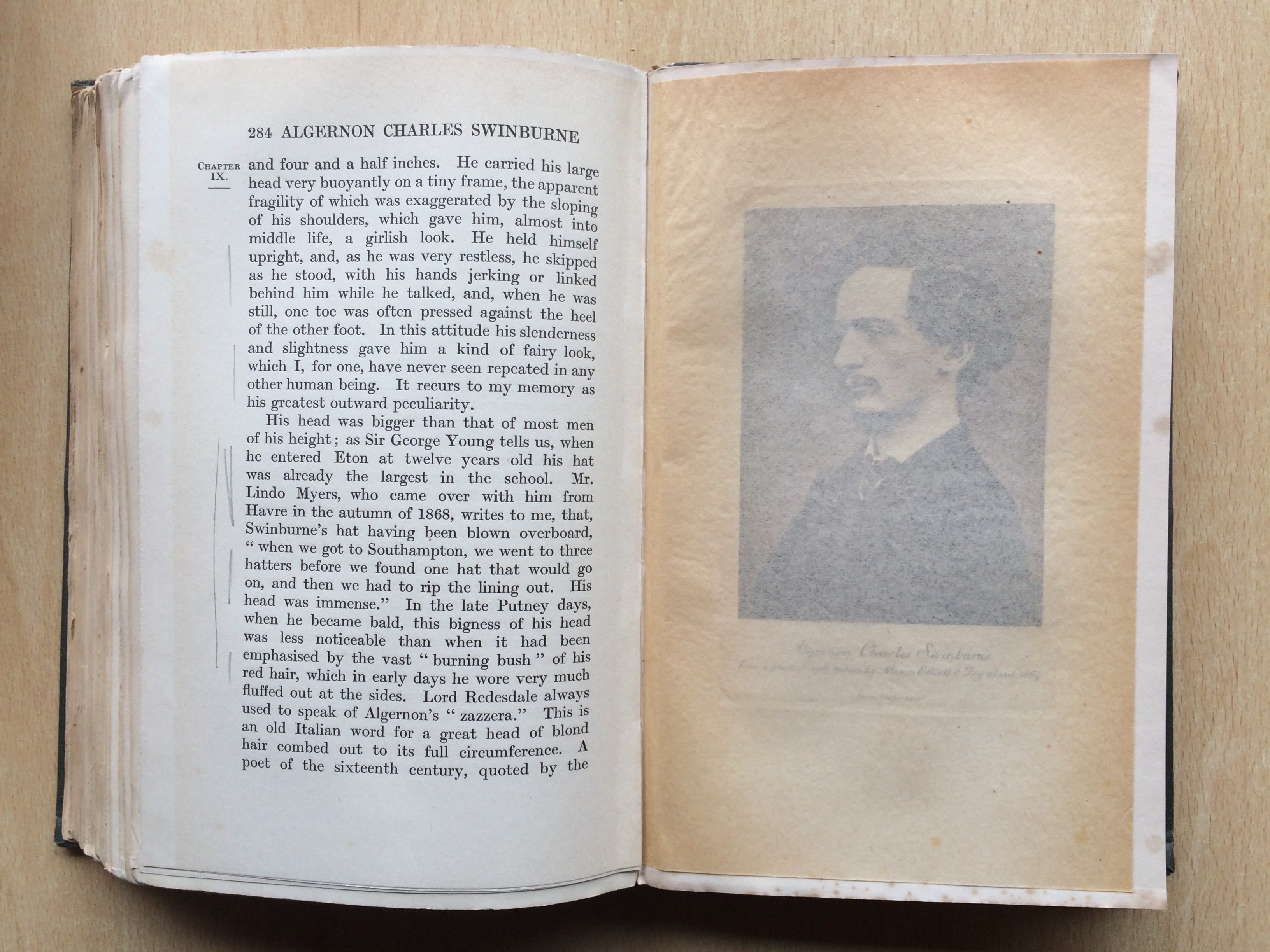

Annotations on a book borrowed from the UEA library by WG Sebald

Annotations on a book borrowed from the UEA library by WG Sebald

In 2015, I invited Michael, who had retired in 2001, back to the Sainsbury Centre to look at what I had managed to retrieve from the archive, and he kindly offered to help identify and sort the photographs and recount the story behind each image. The two exhibitions that I co-curated in Norwich in 2019 to commemorate Sebald’s 75th anniversary, ‘Lines of Sight: W. G. Sebald’s East Anglia’ at Norwich Castle Museum and ‘Far Away, But From Where?’ at the Sainsbury Centre, are testament to this extraordinary but little-known creative partnership and to all who have contributed to, and taken care of, the remarkable collections at the UEA. They are also a demonstration of the commitment of those who worked with Sebald at the UEA to actively maintain his legacy as an ongoing concern. In 2015, Clive Scott established the Sebald Legacy Group to bring together those who knew and worked with Sebald with representatives of the collections at the University to promote and preserve Sebald’s creative and academic legacy in East Anglia.

It is through this group that I have got to know many of Sebald’s friends and colleagues like Gordon Turner, Jo Catling and Stefan Muthesius and through our amicable efforts we have established many new academic, creative and cultural partnerships across the region and internationally. It is thanks to Gordon’s work with the BACW that many amazing video and audio interviews with Sebald are accessible at the UEA, including the 1990 film I described above.

Gordon met Max Sebald whilst they were both waiting to be interviewed for jobs at the UEA in 1970. Jo, the translator of Sebald’s A Place in the Country, started at UEA in 1993. Her first task was to cover Sebald’s teaching as he recuperated from an operation (the story of which is recounted at the beginning of The Rings of Saturn). A generous guide to Sebald archives in Germany, where his books and manuscripts are kept, Jo and her fellow translators at the UEA’s British Centre for Literary Translation have done much to broaden the audience for Sebald’s work. Stefan, like Sebald, a German who made Norwich his home and also an avid photographer, would often spend time chatting to Max as they both waited for Michael to exit the dark room. A celebrated architectural historian, Stefan’s office in the Sainsbury Centre served as the photographic model for Jacques Austerlitz’s in Sebald’s final prose text, Austerlitz published in 2001.

As a group we have spent many congenial and anecdote filled hours together hunting down clues across campus and further afield, piecing together the evidence of Sebald’s time in East Anglia. Guided by Michael’s astonishing powers of recollection, the results of our sleuthing have been edited together into a catalogue of Sebald’s photographic material, Shadows of Reality, published by UEA’s Boiler House Press.

What the various activities of the Legacy Group has shown is, for all the biographical attention given over to his formative time in snowy Bavaria or his solitary wanderings along the Suffolk coast, the interdisciplinary nature of Sebald’s work is also an oblique portrait of the UEA.

For literary pilgrims looking for a waymark, go to the second or third floor of the UEA library, preferable out of term time, find a quiet aisle between the stacks and flick through one of the more interesting looking books. Chances are there will be annotations and underlining throughout, as all good library books should have, but look out for something in German, written in pencil in the margins and if it has an old date stamp at the front, c. 1993, you may have just found the beginning of another Sebald story ready to be pieced together.

Dr Nick Warr is a curator and a film video maker whose work has been shown internationally. Find out more.

Shadows of Reality: A Catalogue of W.G. Sebald’s Photographic Materials (Boiler House Press) is the first-ever volume of the photographs of Sebald and is designed to shed new light on his creative process, chronicling the places, people, and events that shaped his writing life. The book contains an extraordinary combination of film negatives, prints and slides from the University of East Anglia’s photographic collections, the Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach and the Sebald Estate. It reveals the story behind each of the images and their often surprising origins.

‘W. G. Sebald: Shadows of Reality’ is at the National Centre for Writing in Norwich on 12 June 2024. The event is a partnership between British Archive of Contemporary Writing, CreativeUEA and National Centre for Writing.

Find out more about the National Centre for Writing: https://nationalcentreforwriting.org.uk/.