The making of Song of the Reed

WILD TRACKS

How can the arts inform conservation? How can it help us to understand our impact on the environment, inspire us to tackle the effects of climate change?

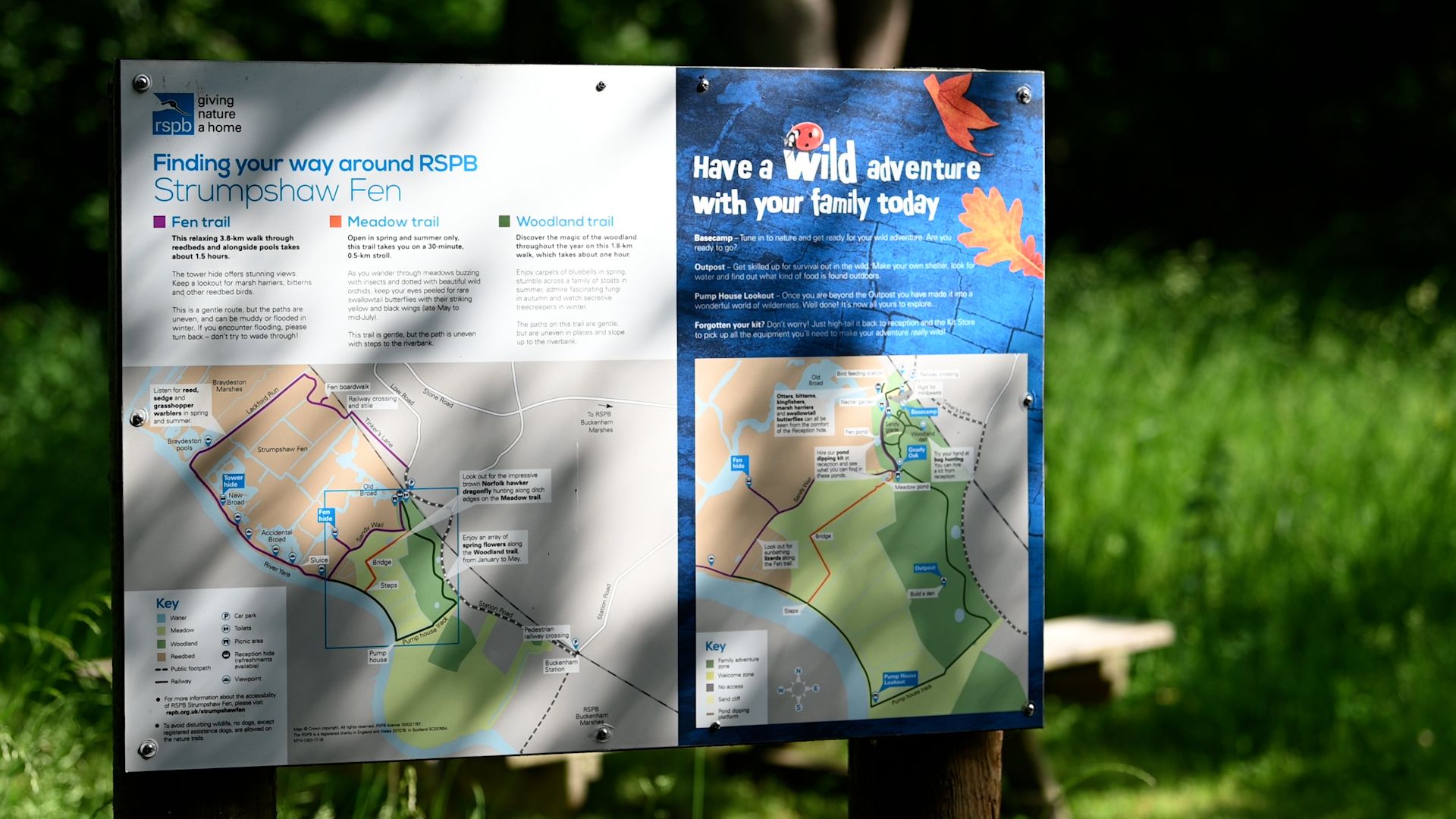

Strumpshaw Fen sits five miles east of Norwich on the River Yare. The reedbeds are home and hunting grounds for bitterns, marsh harriers, and kingfishers, and also one of the final places you can find the Swallowtail butterfly. On a wet and windy day in May this year, Prof Steve Waters and a cast of stars gathered to record the first episode of a his new BBC Radio 4 drama, which focuses on conservation.

This is how it unfolded.

It's 8.30am and I am in RSPB Strumpshaw Fen nature reserve in Norfolk holding down a gazebo. It’s raining, the wind’s up and the forecast’s dire. Me, our radio producer Boz Temple-Morris and sound recordist Alisdair McGregor from Holy Mountain productions are exhausted after a night camping at the reserve, which we arranged with the site manager as part of our onsite recording.

Wind flecked with salt gusts off the nearby River Yare. We’re trying to stop this tent ending up there. I dive into the reed and nettle and drive a peg into peat just as Boz gets a text to announce the actors have arrived. A heron lifts off the fen like a strip of tarpaulin, we leave the gazebo to its fate, and race back to meet them. Now the drama begins.

But how did it start?

Prof Steve Waters at Strumpshaw Fen

Prof Steve Waters at Strumpshaw Fen

On location

Eighteen months ago, I made an application to the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) for a project I gaily called, ‘Song of the Reeds: Dramatising Conservation’. I battled through budgets and workplans, suborning the support of two friendly nature reserves, Strumpshaw and also Wicken Fen in Cambridgeshire, and enlisting theatre company Tangled Feet to help me produce an outdoor show which will land this September at both venues. But I also pitched a four-part drama about an imaginary nature reserve called Fleggwick to the BBC, claiming, hubristically, it would ‘do for conservation what The Archers did for farming’.

Through four seasons, the play tracks the practical work of stemming the global loss of species some have called ‘the Sixth Extinction’. Would the funders bite?

A week before the first lockdown in March 2020 the AHRC told me I’d been successful and in June we got the thumbs-up from the BBC. Game on! In a world of shut reserves, travel restrictions and closed theatres, we had to make a drama out of that crisis and now, a year on, we’re recording Episode One – Swallowtail. Was it wise to centre a radio drama around butterfly that makes no discernible sound?

"In conventional plays nature plays a dutiful bit-part as ‘setting’ and ‘backdrop’ to the foreground of human affairs. Yet here these realms blur in an ecological-dramatical feedback loop"

The actors arrive and assemble in their ‘green room’, a Nissen hut for reserve staff - glamour is not the order of the day - but as the skies open, we huddle here in our masks, read the script and drink coffee.

As the company gathers in waterproofs and walking boots, I’m struck by how unlike the recording of a conventional radio play this is. Audio drama production depends on the ‘controlled environment’, yet here we are in a world of constant sonic surprise: that Yarmouth train sounding its cheery pre-emptive horn, the chatter and clatter of reserve staff going about their business, or the sudden alighting of a gaggle of geese going about theirs.

As a veteran radio dramatist, I’m used to taking a pilgrimage to BBC Broadcasting House in order to enter its sound-proofed environments which provide a kindergarten for the imagination.

The actors do their magic in the crepuscular recording studio where boxes of audio tape stand in for snow, staircases lead nowhere, and doors stand in their frame ready to be slammed shut. Everything revolves around the all-powerful microphone; if a line’s to be shouted, the actor’s dispatched into a corridor of foam that forms an acoustic baffle. Through the sound barrier on the other side of a plate glass wall sit the production team behind banks of blinking mixing desks.

It’s playful but airless, a zone of the mind as much of brute reality, where the physical world is to only to be found in the hours of pre-recorded sound effects lining the shelves. ‘Song of the Reed’ tears up that rulebook. Here location prevails, brute reality crowds in and we’re all in it together. The membrane between fact and fiction is thin as we corral passing reserve staff into taking a part and I find myself ‘acting’ as much as editing the script as we go.

Guest stars

Soon we head out into the reserve chasing my scriptwriting colleague Molly Naylor who plays a reserve volunteer Kay, obsessed with CSI dramas, as she inducts UEA Drama alumni Ella Dorman-Gajic as Tam, a curious student come to help.

Al and Boz, frowning in headphones, thrust the fluffy mammal-like directional boom mike in their path, vigilant for any paper rustle or line-fluff. I hold puzzled reserve visitors back, and the wind sighs its disapproval. Everything becomes a so-called ‘wild track’, those off-script recordings of birdsong, rain patter and ambience, of which there’s no shortage here.

"Our guest stars are creatures on the brink of existence: the Little Ramshorn Whirlpool Snail, the Bittern, the Swallowtail butterfly"

I realise I couldn’t be more delighted about that – after all my project seeks to turn drama and its making on its head. In conventional plays nature plays a dutiful bit-part as ‘setting’ and ‘backdrop’ to the foreground of human affairs, thereby reinforcing the centuries long severance of human and ‘natural’ experience. Yet here these realms blur in an ecological-dramatical feedback loop.

UEA graduate Molly Naylor

UEA graduate Molly Naylor

Sophie Okonedo and Boz Temple-Morris at Strumpshaw Fen

Author Prof Steve Waters

Boz Temple-Morris and Alisdair McGregor

Boz Temple-Morris and Alisdair McGregor

Sophie Okonedo and Mark Rylance

Sophie Okonedo and Mark Rylance

Zaydun Khalaf

Zaydun Khalaf

UEA graduate Ella Dorman Gajic

Ella Dorman Gajic

After all, the very action of this episode is driven by the needs of a reserve on the cusp of change, as ecologist Max Godwin (loosely based on legendary Norfolk naturalist Ted Ellis) dies, forcing his daughter, Liv – Sophie Okonedo – to come home to wind up his affairs. In this task her chief obstacle is Max’s implacable reserve warden, Ian George played with steely grit by Mark Rylance.

Yet, for all the human drama between them as they straddle the fault-lines of modern Britain, the core story is the fate of 50 hectares of reedbed and Broadland, fen meadow and carr, and the 10,000 species resident in its midst. This inversion even holds true in the sub-plot; after all, every multi-part drama needs a ‘guest’ to focus the episode, as in the variably familiar faces that populate the Netflix hit, ’Call My Agent’.

Yet in ‘Song of the Reed’, rather than a Juliette Binoche or Nathalie Baye in the foreground, our guest stars are creatures on the brink of existence: the Little Ramshorn Whirlpool Snail, the Bittern and in this episode Norfolk’s most iconic invertebrate, the Swallowtail butterfly.

Playing second fiddle to nature

I just blithely glossed over the fact that the plays star two of the leading actors of our time but as they wander into the reserve, this miraculous fact hits me. Sophie Okonedo’s an actor of rare wit and emotional precision – for years I’ve been watching in awe her work at the Royal Court in the plays of Martin Crimp and Joe Penhall, or in films from Pretty Little Things to Hotel Rwanda; seeing her set foot in the reserve for the first time is slightly awesome.

And here’s Mark Rylance in pork-pie hat, the man who’s played roles from Thomas Cromwell to the BFG, inspecting (with genuine glee) a display board of RSPB species button badges before navigating with expert ease the vagaries of the Norfolk accent.

"Recording on the Fen was a wonderful experience. It transported me into the world Steve had created"

Yet for all the actors’ gifts in this place we all play second fiddle to the drama of nature, indifferent to our presence. Yes, the real star here is the fen itself and its staggeringly diverse inhabitants, which is why I punctuate the action with the voices of the reeds themselves. The common reed – Phragmites australis – is the signature vegetation of wetlands across the world, a landscape disappearing at a terrifying rate. The Ramsar Convention, instituted 50 years ago to monitor the status of this environment, has recorded a loss of 35% of wetlands since then, which follows centuries of drainage, neglect, even fear, of these places hovering between land and water. Mark’s pledged to advocate for the Wildfowl and Wetland Trust’s exciting proposals for a ‘Blue Recovery’: the creation of ‘a natural infrastructure’ of 100,000 new hectares of wetland in the UK.

For all their aesthetic pull, wetlands are far more effective carbon sinks than forests, habitats for the world’s wading birds, providers of flood alleviation and the filtration of polluted rivers.

Whilst my drama goes deep into this patch of England I want it to speak to the global catastrophe of wetland loss through the sub-plot of Iraqi scientist Sadegh Alwash played by Zaydun Khalaf. He’s my homage to the founder of NGO Nature Iraq, Azzam Alwash, an engineer dedicated to undoing the mortal harm inflicted on the wetlands of Mesopotamia by decades of war.

The future of the Swallowtail

But conspicuously absent today is our protagonist: Papilio machaon Britannicus. The Swallowtail is the largest breeding butterfly in the UK; its creamy veined stained-glass wings with powdery blue and red ‘eyes’ at their base, dazzle all lucky enough to see them. The cold Spring that has retarded all life in the reserve however and we’re recording a fortnight before its chrysalis is scheduled to transmute into butterfly.

I first saw this butterfly thanks to an encounter with Strumpshaw’s founder, ecologist Martin George, before he sadly died in 2016. Martin, an entomologist by training, impressed upon me the global significance of this ‘sub-species’ severed from its continental counterpart Gorganus by the ice age.

Once common across Southern England, it’s lost from everywhere but the Broads and, despite three attempted re-introductions, never re-colonised Wicken Fen and environs where a century ago it thrived.

"The arts can contribute to local and global conversations and the growing awareness about our environmental crisis"

As local enthusiasts like the Norfolk Butterfly Recorder, Andy Brazil, or global advocate for the Swallowtail, Mark Collins, note, the species’s population fluctuates according to the fate of its food-plant milk parsley, and this is in turn threatened by climate change driven sea-level rise.

Will this beautiful creature even survive the next few decades, as the freshwater ecology of the Broads is threatened by storm surges that force salt-water into their midst?

Epilogue

The time has come to seek out the benighted gazebo; the company heads into the fen to record the episode’s central scene and I’ve enlisted the head of the mid-Yare reserve, Tim Strudwick, to play a vox pop part. It’s a public stand-off between Ian and Nikki (played by Karen Hill) the head of ‘WildScapes’, an invented conservation organisation whom Liv is wooing. But we’ve another role to fill and time is short – who will perform it?

Step forward newly arrived volunteer at Strumpshaw, former Data manager Adrian Samuels, now living in its Marshman’s cottage as he’s trained to be a professional conservationist. I expect him to say ‘no’ but his face lights up at the chance, and Tim’s raring to go. As we approach the gazebo the rain spits, the wind picks up and the guy ropes strain; a frisky egret tumbles in the air currents and the highland cattle patrol the meadow, chewing with idle indifference. Mark and Karen and Sophie tear into each other, Al tilts and flips the mike, and I cue in Adrian and Tim who hit their marks like pros; around us the reeds roar in the wind as if we were out at sea.

Am I wrong to imagine that the percussive song of Sedge and Reed Warbler is their contribution as secret sharers in this drama? I only know that later today (21 June) when the show hits the airwaves, I’ll be seeing Strumpshaw’s magnificent sweep in every word and every sound. And I hope you will too.

The cast and crew of Song of the Reed

The cast and crew of Song of the Reeds

Professor Steve Waters is a playright and Professor of Scriptwriting at the University of East Anglia. He works for stage, radio and screen and has been described as ‘one of the UK’s most accomplished political playwrights’. He is perhaps best known for The Contingency Plan, a diptych of plays about climate change. Find out more about Prof Waters' project to explore climate change through creativity.

Affected by eco-anxiety? Understand more about climate anxiety, learn about ways to alleviate it, and find out about a new partnership between UEA, Mind and the Climate Psychology Alliance designed to help tackle it.

Photos: Cast and crew by Dave Guttridge; wildlife by Ben Andrew (rspb-images.com) and Matt Wilkinson (rspb-images.com); Neil Hall